Underwater Programs & Inventions

Jump to Postwar Years | Underwater Exploration | Harbor Branch | Submersible Technology | Clayton Link

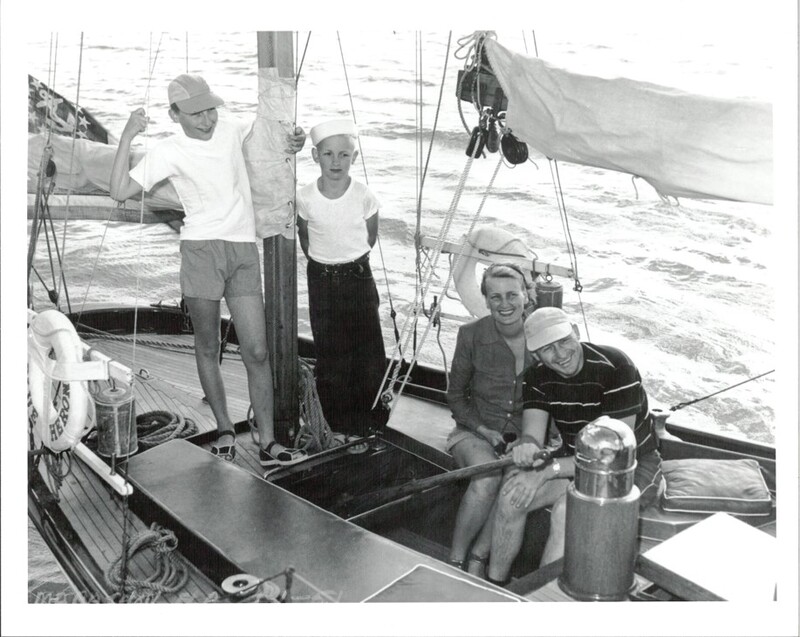

As Link Aviation continued to grow, so did Link's interest in sailing, diving, and commerical aquatic inventions. The scale of their industry with its rapid manufacturing prevented Link from fully engaging in the hands-on type of engineering he loved, and he found that the ocean could offer all that he was missing. He still maintained a steady presence at Link Aviation but more and more, Ed and Marion and their two sons, Bill and Clayton, escaped to Florida aboard their sail boat, Blue Heron.

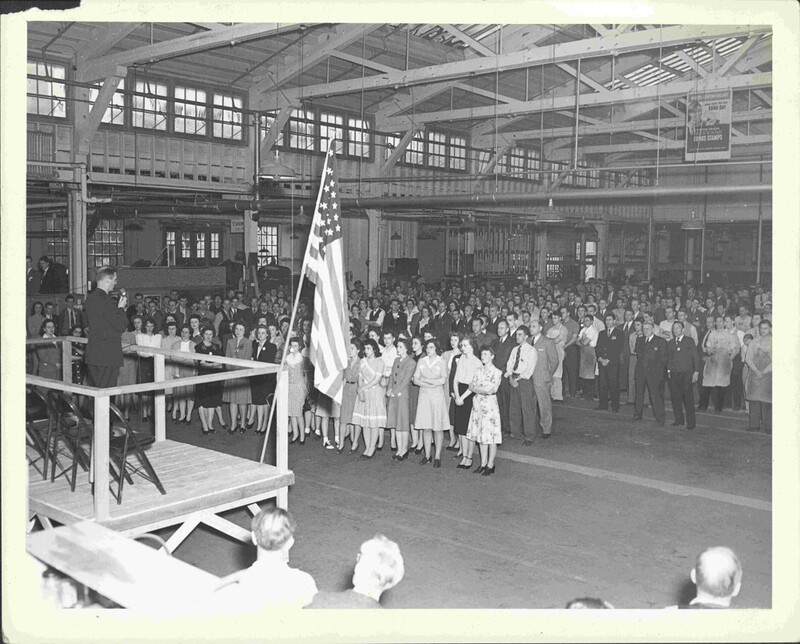

The postwar transition that Link had dreaded was avoided when the simulator industry captured the interest of commercial airlines, who required a steady stream of flight trainers. The outbreak of the Korean War also ensured that Link’s company would comfortably endure the years to come. In 1954, Ed and George Link sold Link Aviation to General Precision Equipment Corporation, and Ed finally turned his sights fully to the sea.

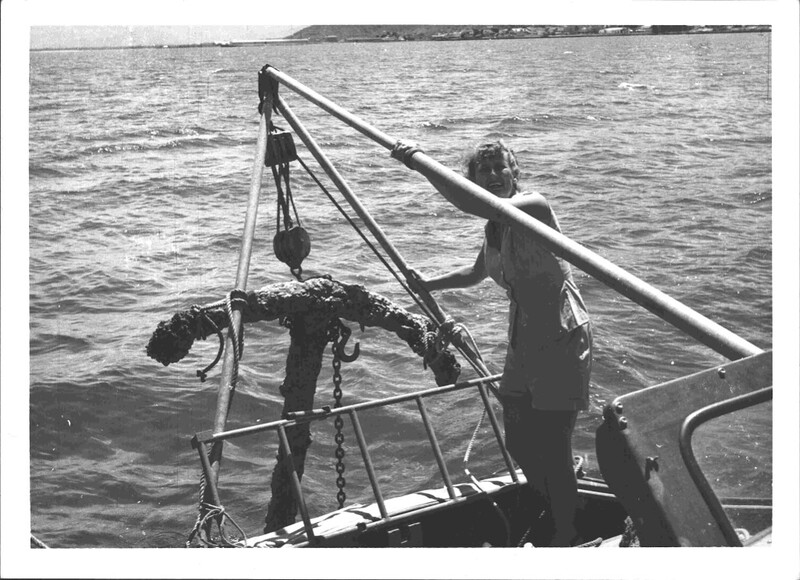

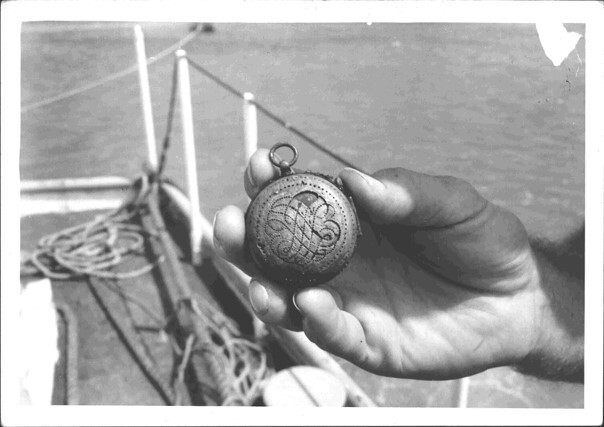

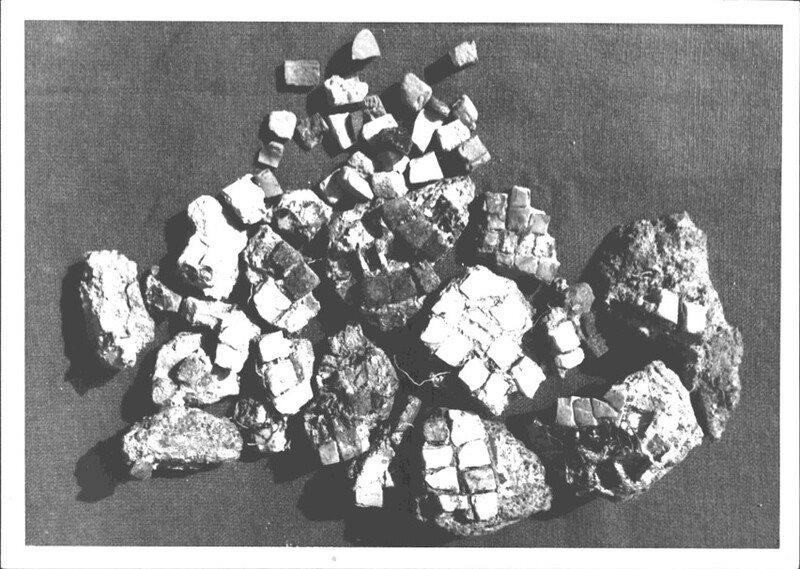

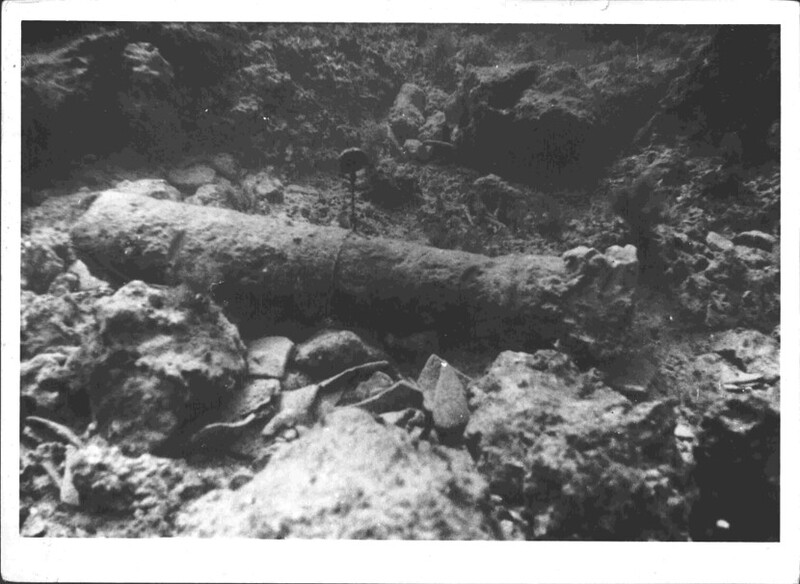

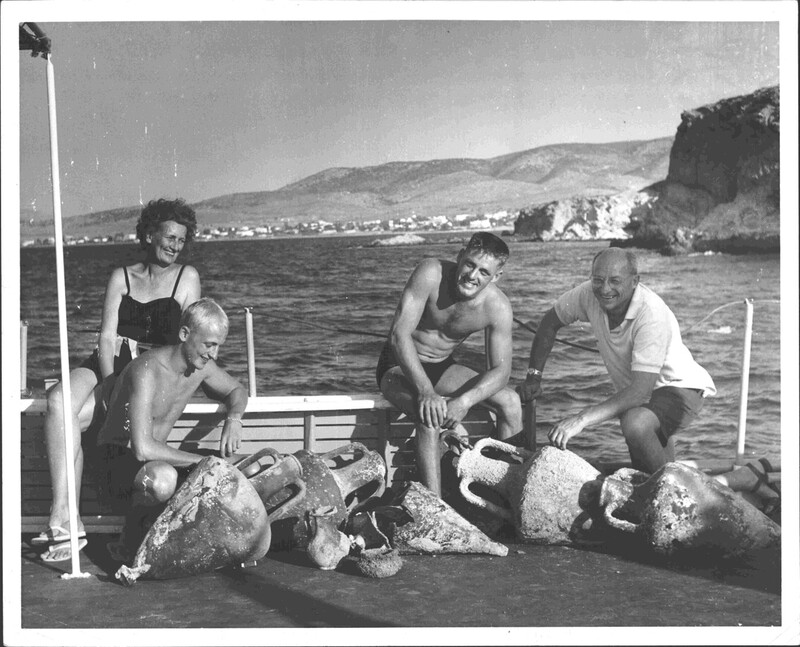

Selling Link Aviation allowed Ed Link to devote more time to diving and treasure-trawling with his family. Ed was especially interested in wrecks of Spanish galleons off the coast of Florida and the Florida Keys for their treasures and historical artifacts.

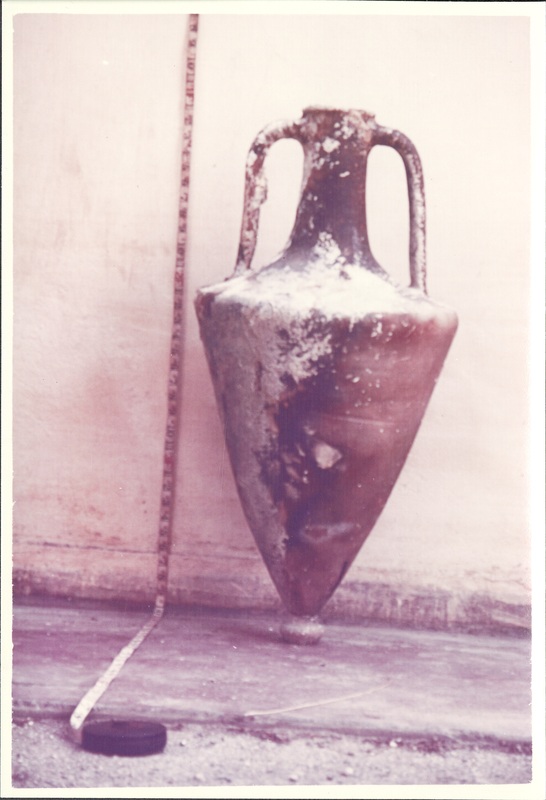

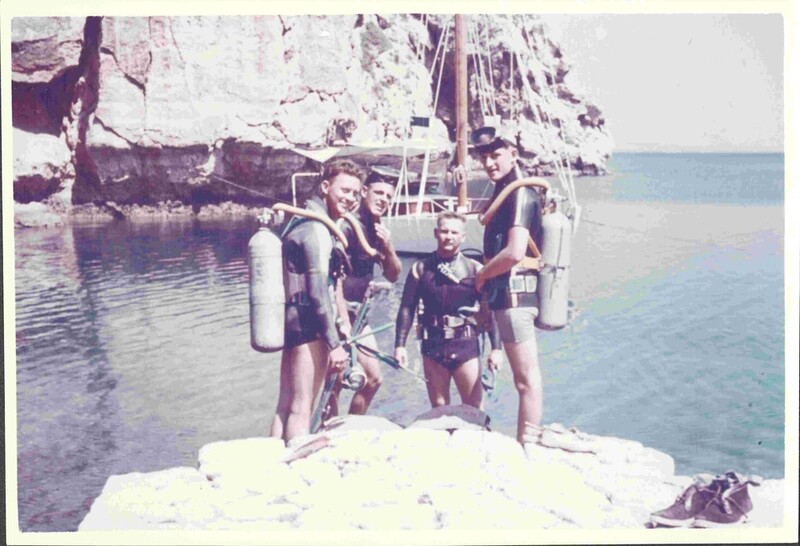

The Link family spent time exploring areas in the Bahamas, Haiti, Jamaica, Israel, Greece, Sicily, France, and the Silver Shoals, a large expanse of coral reef near Hispaniola. They engaged in many archaeological explorations to discover landmarks, wreckage, and other historic objects. In 1952, the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society sponsored an excavation of the sunken city of Port Royal, Jamaica. Link and U.S. Navy divers found hundreds of artifacts that made valuable contributions to the historical narrative.

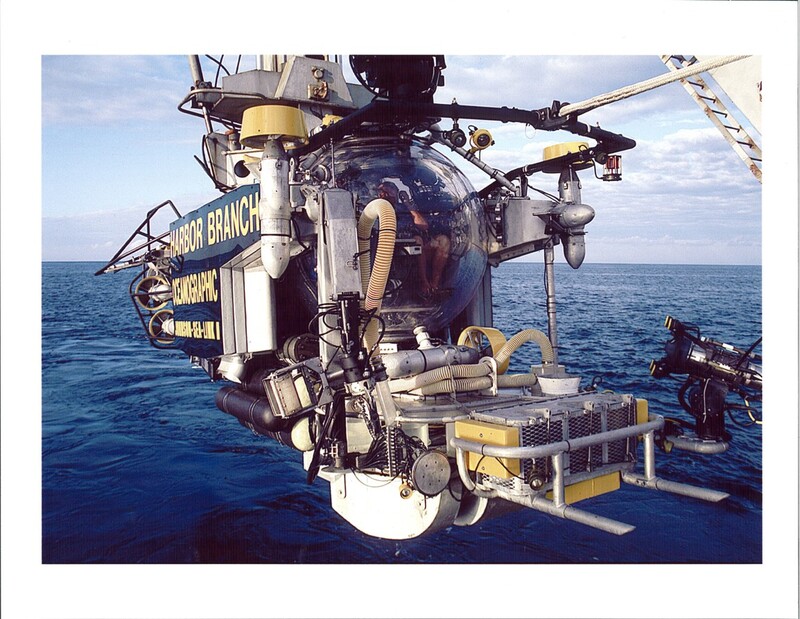

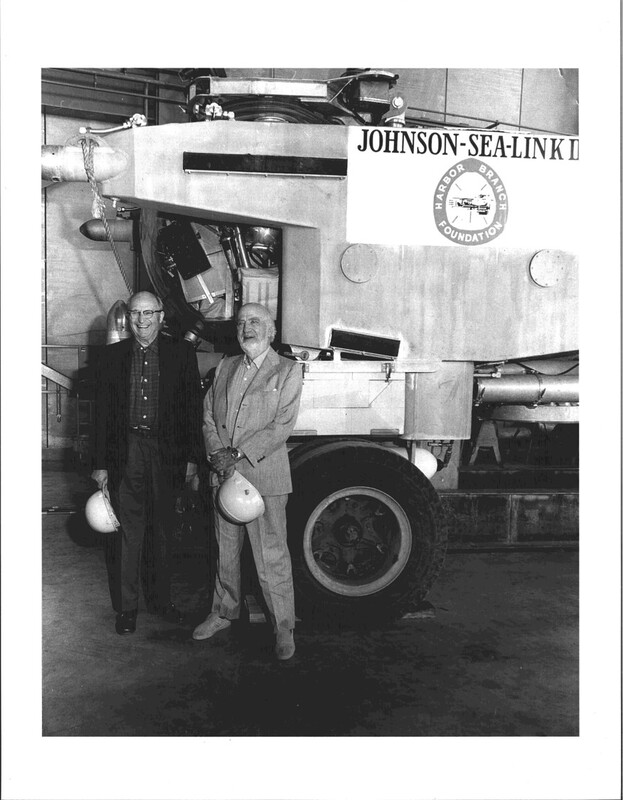

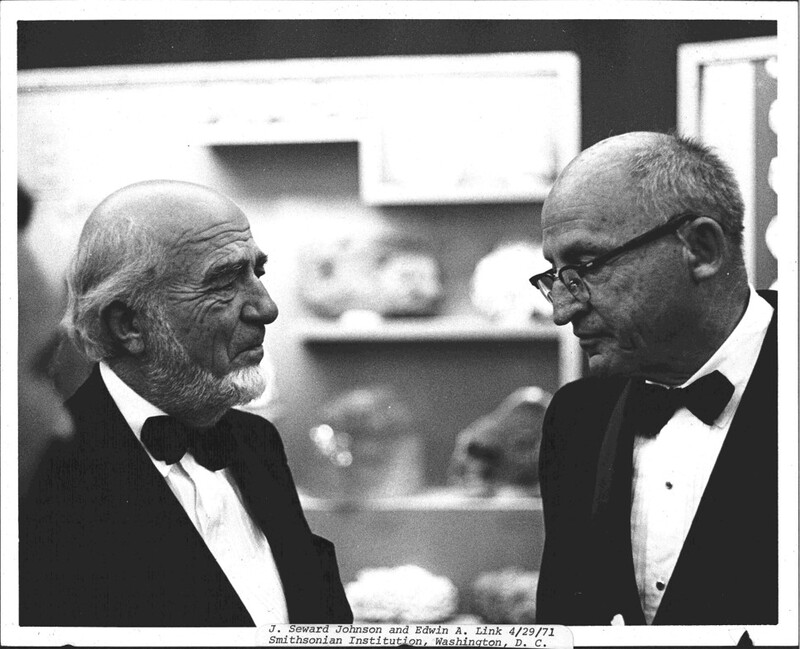

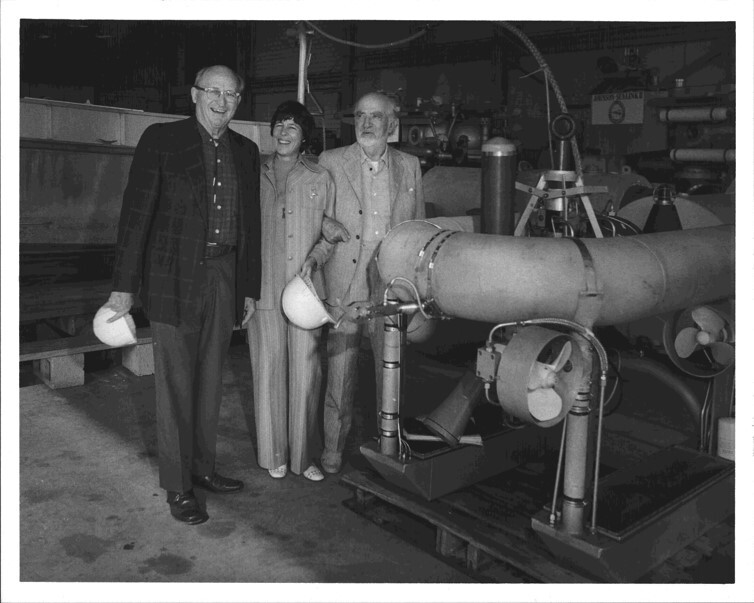

Ed Link's partnerships with other divers, marine scientists, and companies that specialized in ocean research blossomed into initiatives like that of the Harbor Branch Foundation (later renamed the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Insutitution, or HBOI). Founded in 1971 by J. Seward Johnson with encouragement from Link, it established a permanent oceanographic research facility in Florida. Link's primary focus was the design and creation of new submersibles, including the Johnson-Sea-Link which weighed 18,000 pounds and could bring divers down 1,500 feet beneath the surface of the ocean. The Smithsonian Institution retained this vessel, while Harbor Branch launched the JohnsonSea-Link II in 1975. You can see more of what Ed Link was working on by exploring the Submersible Technology section below.

Today, the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Insitute Foundation supports HBOI and works in conjunction with Florida Atlantic University to fund oceanographic research. The Link family, especially Ed Link's sister, Marilyn C. Link, worked closely with the Foundation to explore what they thought was the next great frontier: the deepest parts of the ocean.

Link continued inventing new types of diving and submersible equipment that would allow divers to both stay underwater longer, and reach deeper depths of the ocean. He continued to nurture partnerships with the Smithsonian, the United States Navy, and other research groups that were interested in the new horizons Link envisioned for the future of underwater exploration.

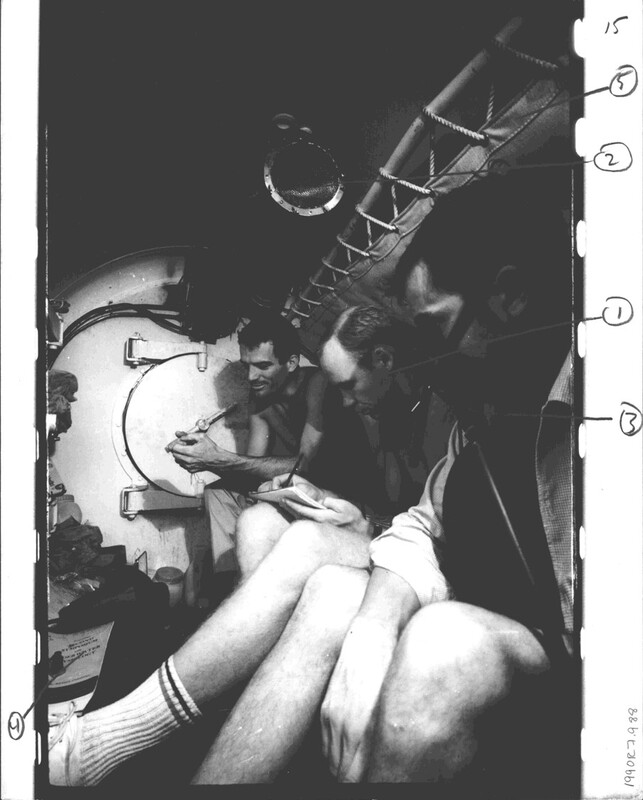

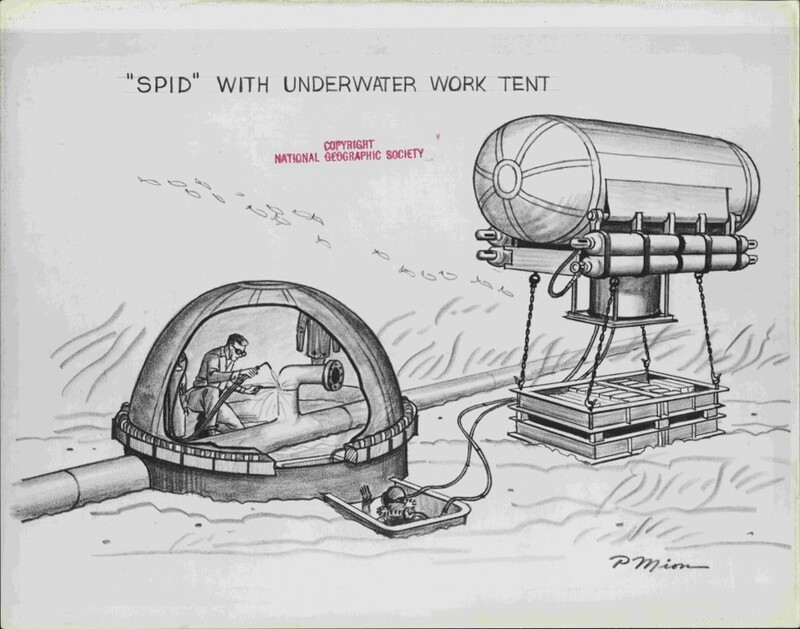

Some of Link's inventions include submersible decompression chambers, or SDCs; a Submersible-Portable-Inflatable Dwelling (SPID), underwater workspaces like the IGLOO, and early iterations of other submersibles, like the Perry Cubmarine. Some of of Ed Link's inventions served a very special purpose: one machine, CORD, was built after the death of his son Clayton.

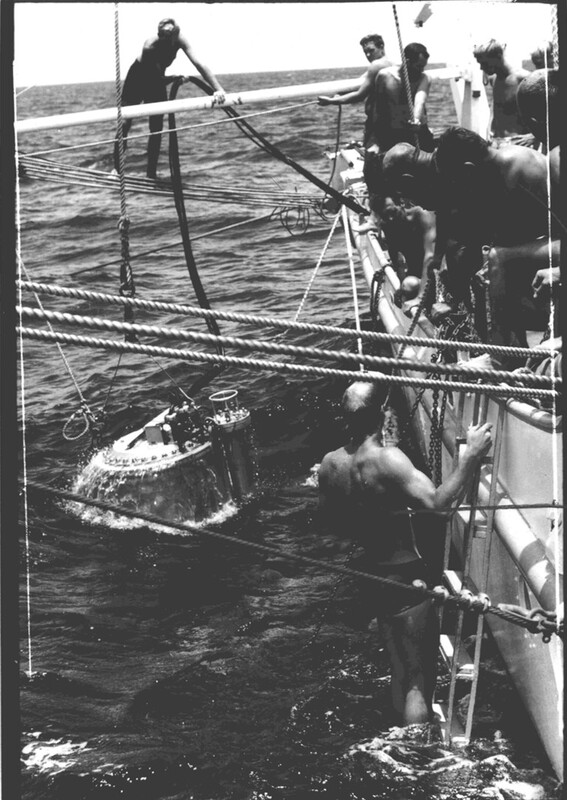

The Link family took part in hundreds of diving expeditions and archaeological excavations, the complexity of these trips growing in step with innovations in diving and submersible technology. In 1973, however, one of these excavations ended in tragedy.

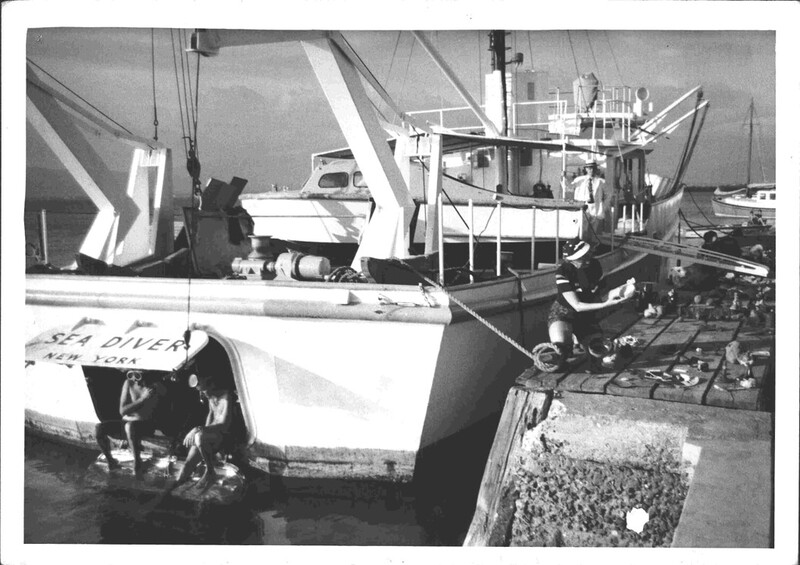

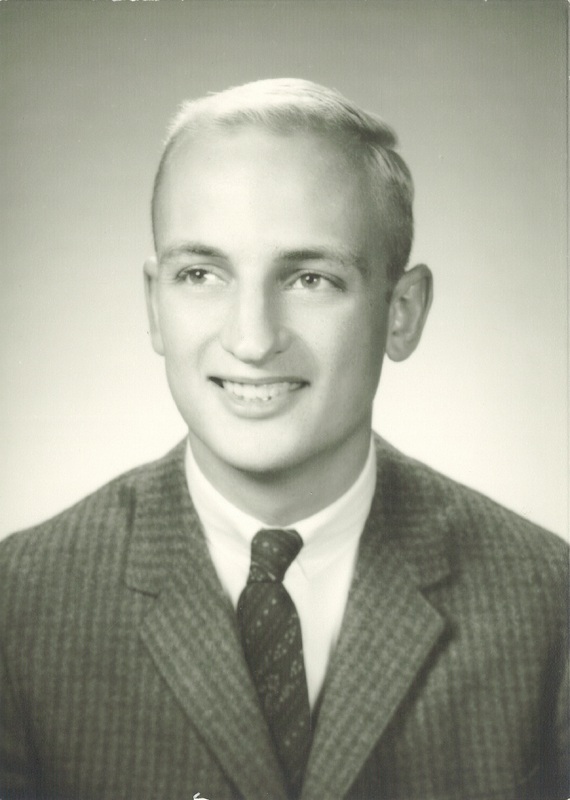

Edwin Clayton Link was Ed and Marion's younger son, who was an experienced diver and had accompanied his parents all over the world on their travels. One morning in June, off the coast of Key West in the Florida Keys, Ed and Marion sat aboard the Sea Diver while Clayton, fellow diver Albert D. Stover, pilot Archibald "Jock" Menzies, and marine biologist Robert Meek went down in the Johnson-Sea-Link to explore an artificial reef made from World War II wreckage. Clayton and Stover were in an aluminum "lockout chamber"- the environmental compartment divers would use to pressurize their surroundings before leaving and returning from a deep dive.

That day, the Johnson-Sea-Link became entangled in the cords, wires, and other wreckage that had created the reef, and was unable to resurface. The men chose to wait for the help that was on the way - Clayton and Stover specifically decided not to pressurize and leave the chamber, as they had no wetsuits to protect them from the cold and not enough oxygen. But the unexpectedly strong Gulf currents prevented the Navy and other rescuers from reaching the submersible until an impossible 32 hours had passed. The aluminum lockout chamber took on the cold temperatures of the water, and when the submersible's carbon dioxide scrubber failed, Clayton and Albert Stover died before help could arrive.

Ed and Marion grieved the loss of their son, but found strength in innovation to ensure something like this would never happen again. Link invented the CORD- the Cabled Observation and Rescue Device, equipped with cameras, lights, and cutters that could slice through the very sort of entanglements that had taken the life of his son. Groundbreaking in its rescue capabilities, the Links contributed to the growth of oceanic technologies with safety and accessibility always at the forefront of their minds.