Earhart to Dickens: The Monday Afternoon Club as Stewards of Culture during the Depression

By Dillon Eggleston

The Monday Afternoon Club was a women’s club, organized 1890 to promote education, literature, and the arts through discussion of magazine articles every Monday, devoting one Monday each month to current topics. To supplement their discussions, the Club hosted lectures open to Binghamton’s community. In the wake of the Great Depression, the Club restructured internally, consolidating their number of departments. These departments determined the types of, and topics for the events they would host. Decreasing from nine to six departments, the Club focused on the quality of events, held within a narrower range of topics. They consolidated from the Departments of Art, Civics and Economics, Current Events, Drama, Literature, Music, Nature Study, Philanthropy and Education, and Hospitality to the Departments of Art, Drama and Literature, Music, Travel, Social Sciences, and Current Topics. After consolidating, the Club kept most of their cultural departments while reorganizing their civic departments. Through their emphasis on culture, the Club sought to steward, or manage, Binghamton’s cultural development and recover their budget in the process. This examination raises some questions: What kind of culture did the Club promote in Binghamton? Who was their audience?

Before answering these questions, the Club must be put in a larger context. In 1935, FDR set up the Federal Theater Project, and the Federal Art Project. These projects supported the production of culture through different mediums, especially plays and murals. The projects employed actors, stage hands, and artists, who were unable to find work otherwise. The Monday Afternoon Club showed their support of the arts through lectures and other events they hosted or contributed to, such as movie screenings and dances. While the Club never directly benefitted from FDR’s projects, the federal government and the Club both wanted to develop the culture enjoyed by people. In the case of FDR, his New Deal programs fostered the development of American culture.

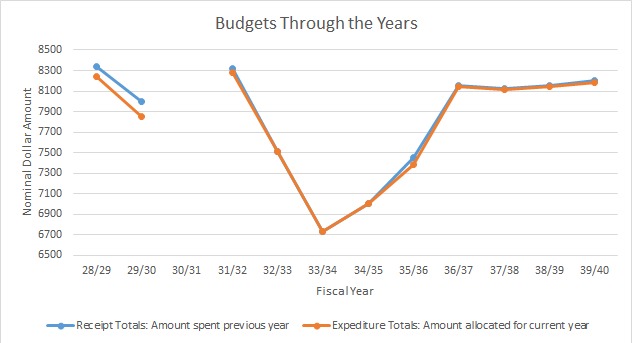

The Club, on the other hand, attempted to provide a means to escape the realities of the Great Depression through their support of the arts. Unable to remain invulnerable to the effects of the Great Depression, the Club saw a huge hit to their budgets in the 1932-1933 and 1933-1934 fiscal years. In the 1930s, the Club spoke publicly about their “disapproval of current films,” instead opting to support film adaptations of literature, such as Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Some culturally influential movies of the 1930s include Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) and Mutiny on the Bounty (1935). The former opens with the sheriff confiscating (ripping off) the dancers’ costumes, who dressed as coins. The latter explores Westerners’ interactions with an economic system in opposition to capitalism by idealizing the Tahitians, who lack a concept of money, as Hanson discusses in This Side of Despair. With films seen as either too salacious or as romanticizing the “primitive,” the Club desired to show “a film well worth seeing,” such as A Christmas Carol. Although unable to independently fund their own screening, the Club collaborated with other organizations such as the Catholic Daughters of America, Jewish Sisterhood and Hadassah, and Binghamton Council of Parents and Teachers, in a “project to furnish suitable motion picture entertainment for children on Saturdays,” in 1939. The Club integrated themselves into the community and fostered the cultural development of children. The clubs’ acceptable festive entertainment also warns against the corruption of greed while fitting into the structure of capitalism, as Scrooge should be praised for his ability to make his fortune, but criticized for turning his back on his humanity.

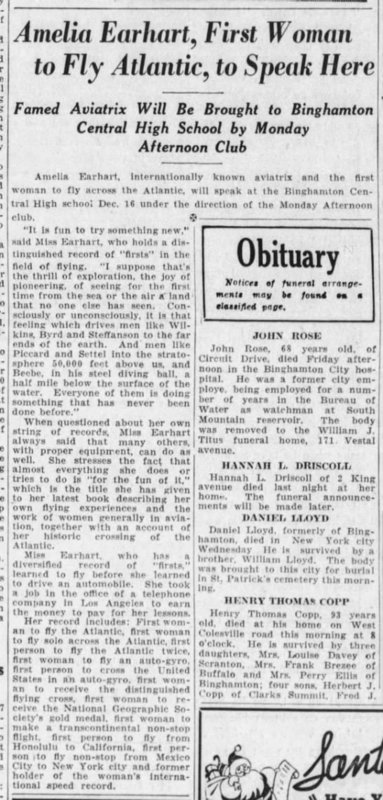

While successful and cheap, (a ticket cost $.10 in 1939, which is about $1.78 in 2018), the Monday Afternoon Club would have needed to share the profits from the above event with the other clubs. In order to bring a larger amount of profit their way, the Club hosted celebrity lecturers, such as Amelia Earhart who came to Binghamton in 1935. In her lecture, she spoke about the benefits of flying as a means of transportation for all, while urging women to “strive for goals outside what is platitudinously known as ‘their sphere.’” Her lecture was well received, with an audience too big for the Club’s playhouse and as a result, Binghamton Central High School hosted her lecture. The Club’s relatively smaller collaboration with another institution within Binghamton’s community was necessitated by their desire to bring in a high profile, high profit lecturer. Earhart reminded the audience about her book in the lecture as well, which provided the audience with more means to get to escape temporarily from the Depression. The success of this “blockbuster” lecturer also allowed the Club to host smaller lecturers, which meant less profit. However, the smaller lecturers would be more closely linked to the Club’s ideals concerning culture, instead of aligning their lectures with a trendy, albeit cultural icon.

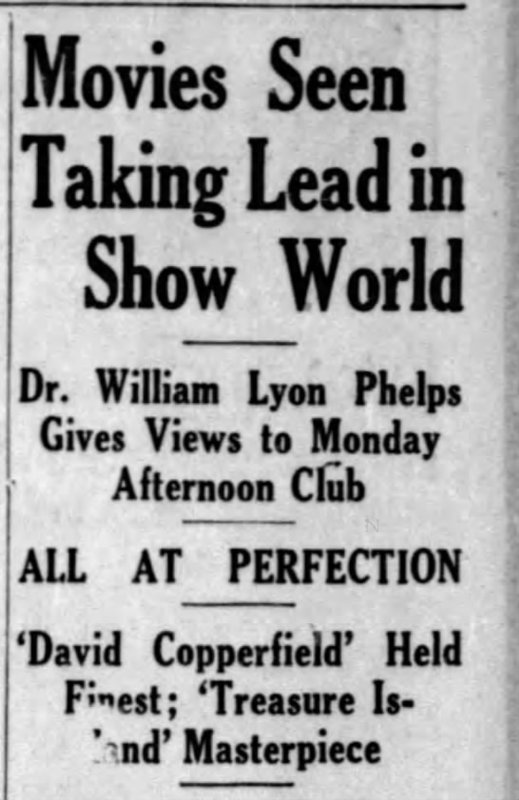

One lecturer the Club hosted by the department of Drama and Literature in 1935 was Dr. William Lyon Phelps, who spoke on “Contemporary Novels and Plays,” such as Heaven’s My Destination, and Escape Me Never, in addition to films like the adaptation of Treasure Island. He promoted the different entertainment mediums in his lecture, but stressed texts over the film, especially lengthy books. He goes on to criticize Heaven’s My Destination, saying “However, the last 500 pages should have been omitted. It is a brilliant book in many ways, but I don’t think it is a great book.” Here, Dr. Phelps’ remark addresses the importance of culture as a way to provide any escape from the Depression, even if the culture consumed is not the best. Its accessibility is what makes it valuable. The affordability, which makes Club sponsored movie screenings accessible, are significant for the same reason.

The Monday Afternoon Club felt the inescapable effects of the Great Depression, as reflected in their budget. Their efforts to restore their budget to pre-Depression levels resulted from efforts to appeal to their audiences using culture as a means of escape. Whether collaborating with other clubs in the area or hosting a well-known name, the Club funded their recovery while also maintaining their roots in lectures concerning literature and the arts. In doing so, they appealed to a range of people including children, people who would see a popular icon and already well cultured people. While not the audience for the federal relief of FDR’s New Deal programs, the Club and these programs both sought to develop and maintain culture in the midst of the Depression. After reorganizing the departmental spread within the club, they developed more profitable for a wide range of audiences for events that lead to a recovery and stabilization in their budget.

Bibliography

- “Amelia Earhart, First Woman to Fly Atlantic, to Speak Here.” The Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Dec. 7, 1935.

- “Amelia Earhart Declares Flying Most Beautiful Way to Travel.” The Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Dec 17, 1935.

- Camen, Lillian, Melba Dickinson, Joan Holleran and Robert Keller. Phelps Mansion: Docent Committee Handbook (Rev. ed. 1998;2003). 2003.

- “Children Will See ‘Christmas Carol’ At Suburban Theatre.” The Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Dec. 12, 1939.

- Davies, Philip and Iwan Morgan. Hollywood and the Great Depression: American Film, Politics and Society in the 1930s, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

- Hanson, Philip. This Side of Despair How the Movies and American Life Intersected during the Great Depression, (Cranbury; New Jersey: Associated University Press, 2008.

- Monday Afternoon Club Minutes. Phelps Mansion Museum Archives. 1928-19-1940.

- “Movies Seen Taking Lead in Show World.” The Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), Mar. 23, 1935.

- Rauchway, Eric. The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction, (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor and Statistics. Databases, Tables, & Calculators by Subject. CPI Inflation Calculator. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.html