Miranda Fatolitis, "Soldiers of Special Interest: Gay Men in the South Korean Military"

Jeram Kang

Jeram Kang was a South Korean man who was conscripted in 2008. When Kang served his mandatory military service, he was groped and harassed by fellow soldiers who found out that he was gay. When Kang went to a commanding officer for help with the harassment, the commanding officer outed him to his entire unit. After he was outed, the commanding officer forced Kang to wear a smiley face pin to mark him as a “soldier of special interest.” He was also forced to shower by himself. Due to the psychological toll of the harassment, he was sent to a military psychiatric ward. Orderlies suggested he pretended to be insane so he could be discharged. Rather than do that, Kang was prescribed antidepressants, attempted suicide twice, and was placed in solitary confinement. After 116 days in confinement, Kang was released from the psychiatric hospital. When Kang was kicked out of the military for psychiatric reasons, his mother sold her house so he could study in London, in a place he felt more accepted. Kang’s case is an example of the discrimination gay men face in the military-discrimination endorsed by Article 92-6.

Article 92-6

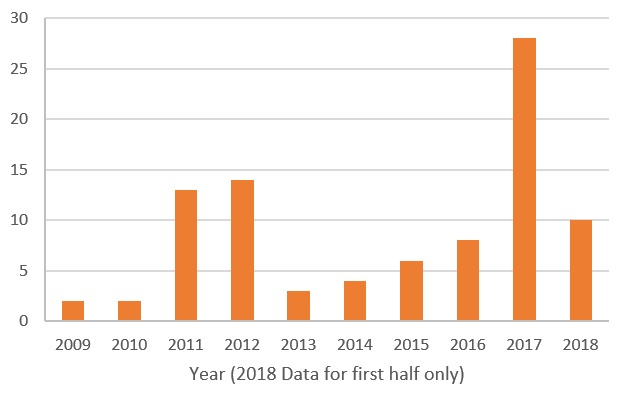

Article 92-6 is a provision of the South Korean Military Criminal Act, which prohibits anal sex. However, this provision is only used to punish sex between men. This prohibition extends to consensual sexual acts and sexual acts which occur between off-duty soldiers and civilians. Article 92-6 is the only area of South Korean legal code where homosexuality is outlawed. Since Jeram’s case, in 2008, the number of men charged with violating Article 92-6 has trended steadily upward, with a record 23 cases in 2017. In the first half of 2018 (the last year for which I could find data), 10 men were charged. During the 2017 case, one man (a captain) was sentenced to prison, although his sentence was suspended. Additionally, the South Korean military raised the punishment for violating Article 92-6 from one year in prison to two years in prison.

Gay Men, Military, and Abuse

The experience of serving in the military with Article 92-6 is an anxiety-ridden experience for gay men. Gay men are forced to serve, but not allowed to be gay. Conscription is mandatory for all able-bodied South Korean men. The disconnect between the environment of the military and the coercive nature of service leads to experiences of unease that predate the actual time of service. Gay men report feeling anxiety about their military service before it begins. Although discriminating against gay soldiers is officially not allowed, the rules grant heterosexual officers much leeway in treating gay soldiers. Gay soldiers face abuse and harassment. Not only are they the victims of homophobic remarks, but they are often victims of the sexual assault and abuse rampant in the military. Gay men are also shut out of the homosocial bonds of service. Like in Jeram’s case, superior officers force gay men to wear identifying markers and shower alone. Once shut out of social bonds of military, gay men experience further alienation. The alienation and abuse that gay men suffer leads to medical problems. Many of the men interviewed for Amnesty International’s report self-harmed and had suicidal thoughts. Once abuse of the military has exhibited in gay men as mental or physical illness, they are pathologized and punished, often assigned the label “soldier of special interest.” The label “soldier of special interest” is assigned to soldiers who are believed to have ill-adapted to military life. In the case of gay men, they have failed to adapt by not conforming to the heterosexuality of the military environment. Anecdotally, gay men say they were punished for not being appropriately masculine, because of their homosexuality. These experiences suggest that gay men are targets because their difference makes them seem like they need discipline to conform to an ideal of acceptable manhood.

"Militarized Modernity" and Acceptable Manhood

Men who fail to conform to the ideals of the state are threats to national security. Within the historical context of South Korea, military service is an essential component of acceptable manhood. Before World War 2, Korea was colonized by both Japan and the West. The conscription system began in 1949. Then, in the 1950s came the Korean War, which kickstarted South Korea’s state of perpetual war. Although the South Korean government historically framed North Korea as the “ultimate enemy,” it is also South Korea’s closest neighbor, upping the perceived security risk. The constant state of war with North Korea is the most common justification for not changing the mandatory conscription system. All men must have a physical determining military suitability, and official documentation is used for conscription. In fact, this method of documentation derives from the military dictatorship in South Korea in the 1970s. Until 1999, serving in the military granted extra points for employment. Today, military service counts as work experience, and not serving is “points against” for men seeking employment. Seung-sook Moon refers to this system as “militarized modernity.” As part of its desire to shed its role as a feminized, colonized body, the South Korean government seeks the national image of a masculinized agent. Gay men in the military fail the national image by failing to portray a hypermasculine soldier ideal.

Unlike in Turkey, where this failure to conform to masculine ideals renders men "disabled" and unfit for service, they must still serve, and face discrimation. But because the military is constructed as a “universal space” of South Korean manhood, the act of criminalizing homosexuality in the military shapes civilian life and constructs homosexuality as an identity that is un-Korean. Amnesty International, in its report, says that “Homophobic and transphobic individuals can view this law as tacit permission to target LGBTI people inside and outside the military. Discrimination and harassment can and does extend to South Korean organizations and events supporting LGBTI rights.” Sexual orientation was removed from the Korean Human Rights Bill in 2007. Conversion therapy is still widely used, and same-sex unions are not recognized. Opponents of repealing Article 92-6 claim that repealing it is a “threat to national security.” As long as Article 92-6 remains in force, gay men will face homophobia outside and inside military life.

Bibliography

Amnesty International. Afghanistan: Serving in Silence: LGBTI People in South Korea’s Military © Amnesty International 2017.

Cho, John and Kim, Hyun-young. “The Korean Gay and Lesbian Movement 1993-2008: From ‘Identity’ and ‘Community’ to ‘Human Rights.’” In Gi-Wook Shin and Paul Y. Chang eds. South Korean Social Movements: From Democracy to Civil Society (Routledge, 2011).

Choe, Sang-hun. “In South Korea, Gay Soldiers Can Serve. But They Might Be Prosecuted.” The New York Times, July 10, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/10/world/asia/south-korea-army-gay.html. Accessed 11/11/2019.

Han, Ju Hui Judy and Jennifer Jihye Chun. 2014. "Introduction: Gender and Politics in Contemporary Korea." Journal of Korean Studies 19(2): 245-255.

Moon, Seung-sook. Militarized modernity and gendered citizenship in South Korea. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

Na, Tari Young-Jung. Translation by Ju Hui Judy Han and Se-Woong Koo. 2014. "The South Korean Gender System: LGBTI in the Contexts of Family, Legal Identity, and the Military." Journal of Korean Studies 19 (2): 357-377.