Xinyi Wang, "Impacts of Reproductive Technology on Inequity and Public Health in Asia"

Introduction

Reproductive technology includes assisted reproductive technology, prognostics, contraception, and others. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) refers to technologies that use medical aids to help infertile couples conceive. ART includes artificial insemination (AI), in-vitro fertilization, and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) and derivative technologies of them. Prognostics can provide pre-diagnosis for the chance of pregnancy. It is able to monitor the associated sexual biomarkers in females, provide semen analysis in males, and predict fetal sex and potential diseases. Contraception is a way to enable people to control their fertility by medical or technical means.

Origins

Flying insects have practiced artificial insemination (AI) in plant reproduction for many years. Later, it starts to be a method of inserting sperm into the reproductive tract of female animals in a non-sexual manner with a natural combination of eggs and sperms. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and his assistant were the first people to have eyes on sperms, which they called “animalcules” in 1678. One hundred years later, Lazzaro Spallanzani successfully performed insemination in a dog in the year 1784. Another decade passed, Walter Heape and other scientists reported the application of Artificial insemination (AI) on animals besides dogs (Foote, 2010).

In-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) refers to the technology to fertilize the male and female gametes (sperm after capacitation and egg) outside the female body. A pre-stage embryo will be developed, transferred back, and placed into the uterus of the female. After successfully applying this technology to rabbits by Mingjue Zhang, Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe started to study in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) technology on humans. On July 25th, 1978, Lesley Brown gave birth to the world’s first IVF baby, Louise Brown. In April 1985 and December 1986, Taiwan and Hong Kong have also had successful births of IVF babies. Later, on March 10th of 1988, the first IVF baby on China mainland was also born in the Reproductive Study Center led by Professor Lizhu Zhang at the Third Hospital of Beijing Medical University, which is the start of Chinese assisted reproductive technology research.

"The Oldest Mother"

On May 25th of 2010, a woman named Hailin Sheng broke the Chinese record of being the oldest mother (now renewed). She gave birth to her twins at the age of 60. Some might ask how and why did she decide to have kids at this age? The answer is the grievance over her daughter. Sheng was living a happy life with her husband and daughter, and she had just recently retired in 2005. Unfortunately, a gas leak happened to the newlyweds on the night of their wedding, causing the couple to pass away due to carbon monoxide poisoning. Sheng was struck by the sudden loss of both her daughter and her son-in-law; she almost wanted to take her own life as well. Seeing Sheng falling apart, some of her relatives and friends suggested that she could consider having another baby and that there might still be medical procedures suitable for her, even if she cannot conceive naturally anymore. After numerous visits to hospitals all over China, Sheng finally found one fertility center that decided to take on her quest. They decided that it was the best option to prepare Sheng for an IVF procedure. Although Sheng did suffer much more significant side effects comparing to normal mothers due to her age, she did successfully give birth to her twins, named Zhizhi and Huihui. Sheng and her twins are an example of how far assisted reproductive technology has come and how it is helping people on their journey of having their babies. However, this also drew my attention to other possible solutions for others like Sheng or couples struggling with infertility in general – surrogacy.

Surrogacy

In just 40 years, assisted reproductive technology has continued to develop and is more and more mature today. From a World Health Organization (WHO) report, infertility affects approximately 13% of women and 10% of men. Infertility in China accounts for 10% of the married couples. This number doubled from the 4.8% shown in a consensus in 1984. The surrogacy industry began to emerge with the increasing need for assisted reproductive technology. A surrogate mother can be defined as a woman who conceives and transfers the delivered baby to intended parents, and the surrogate mother waives all rights to the child as a mother. There are two forms of surrogacies: traditional surrogacy and pregnant surrogacy. In the traditional way, a surrogate mother carries the sperm from the intended father (usually through artificial insemination methods (AI), rarely through sexual intercourse directly) or a donor’s sperm (Trimmings et al., 2011).

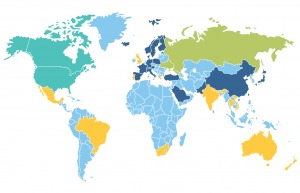

For surrogacy, laws and policies vary among different countries. In this map, the Teal color shows areas where surrogacy is entirely legal for intended parents, including citizens and non-resident aliens, such as the United States and Canada. The Green color shows areas where surrogacy is legal to only citizens and certain (medical requirement) international parents who are infertile, such as Russia. The Yellow color shows areas where surrogacy is restricted legally for citizens and international parents to be, like India, Brazil, and Australia. The Light Blue shows areas where no regulations are in place regarding surrogacy under the authority. Though commercial surrogacy may still happen, which counts as a “grey industry.” Most countries around the world are under these circumstances, reflecting the urgent need for official surrogacy laws and regulations. The Dark Blue shows areas where all forms of surrogacy are banded and deemed illegal according to regulations or policies. China and the majority of European countries are examples of this.

The unhealthily fast development of society has created a high level of infertility, but the advancement of medicine has drastically changed the way of human reproduction. Assisted reproductive technology and surrogacy, while bringing the hope of “lineage” to millions of people struggling with infertility, have also made newborns be “exiled” from the surrogate mother’s womb and resulted in inequity and public health issues.

Take China, for example, “Made in China” is well-known all over the world partially because of the low prices. For years, western societies have sought cheap labor from China. However, now Chinese parents are turning to the US and other countries for commercial surrogacy. In China and the majority of Asian countries, all kinds of surrogacy are banned. But in the surrogate industry, money talks. Wealthy Chinese couples turn to those countries where commercial surrogacy is entirely or partially legal.

Moira Weigel interviewed Dr. John Zhang, the founder of the New Hope Fertility Center -- one of the busiest fertility centers in the US -- located in New York. He emigrated to the United States in 1991 from mainland China. He had basic medical training in Chinese universities, specialized medical training in England, and did his clinical practice in the United States. New Hope Fertility Center was founded in 2014. Together, five doctors from this center conduct over 4000 IVF procedures every year. A couple, Min and Kai, are intended parents from China. They are both professionals in their forties from Beijing who have failed several times trying to have a baby the natural way. They ended up picking a surrogate mother of their yet to be born daughter, Sarah, from New Hope Fertility Center. In the article, Weigel mentioned that the couple plans to wait until Serah turns five or six to emigrate to the United States as the parents of a surrogate “anchor baby.” Immigration based on this kind of surrogacy is already and will continue to impact Asian diasporas around the world.

However, surrogacy brings more than just hope for society. Reported by Stephen Chen in 2017, surrogate motherhood has become an illegal family industry in a poor Chinese village near Wuhan, a city at Hubei province, China. There, more than 100 women were bearing fertilized eggs for couples that they have never met. These shady surrogacy agents often operate in the black markets, posing themselves as health consultants, and charging couples more than 800,000 RMB ($115,000) for a healthy boy. In contrast to the steep price tag, the surrogate mothers will get only a small cut of the money – usually between 100,000 and 200,000 RMB ($15,000 to $30,000). Because surrogacy is not legal in China, these women are being used, despite if they had a choice or not. They are being exploited in various forms, yet they have no way to protect themselves. The worst part is that compared to baby girls, most intended parents prefer baby boys. Therefore, gender selection technologies are used before most births to determine the baby’s gender to accommodate the preference of the intended parents. Which, in turn, will aid in worsening the gender imbalance that is already serious in Chinese society today.

In India, one of the biggest countries as a home for surrogate mothers, women’s health is threatened by the condition of multiple gestations. Two or even more embryos are usually implanted into the surrogate mother’s uterus in order to increase the rate of success. If all of the embryos happen to survive, a multifetal pregnancy reduction procedure will have to be performed, which brings considerable harm to these women’s health.

In 2014, a surrogate mother from Thailand complained that she had just given birth to twin boys. However, one of the babies with Down syndrome was unfortunately rejected by the intended parents. They ended up only bringing the healthy one back to Australia with them. What would happen to this baby that was unwanted by the intended parents? Who should be held responsible for this kid?

Reports have also revealed the kind of treatment that some surrogate mothers received. If they fail to comply with all of the company’s strict regulations or have a miscarriage, the company will refuse to pay or compensate them. That should not be the way to treat the surrogate mother’s body and health.

Genetically Edited Babies

Jiankui He is an associate professor in the Department of Biology of the Southern University of Science and Technology. In November 2018, he revealed the birth of two genetically edited infants, Lulu and Nana, whose CCR5 genes were edited to gain immunity to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The technology used in this research is called CRISPR/Cas9 (Doudna et al., 2014). He and his team edited the CCR5 genes, which had been proven to be related to AIDS, so that Lulu and Nana can be immune to AIDS. From March 2017 to November 2018, He recruited eight couples as volunteers (HIV-positive male and negative female) to participate in the experiment, offering an opportunity to fulfill the desire of patients with AIDS for healthy offspring as an incentive for them to participate in this experiment. Finally, two volunteers got pregnant, and one gave birth to Lulu and Nana. The product expressed by the CCR5 gene is a protein on the surface of white blood cells, the CCR5 protein. The process of entering and infecting host cells with the R5 HIV requires CCR5 protein to take place. A mutation of the CCR5 gene, called CCR5-Δ32, has a deletion of 32-base-long genes in the human body. Its expression product cannot be detected and bounded by HIV. So, animals that are carrying the CCR5-Δ32 gene will be immune to R5-type AIDS (Allers et al., 2011; Hütter et al.,2009). However, the role that CCR5 plays in human immunity health has not been thoroughly studied yet.

Although theoretically speaking, carrying the CCR5-Δ32 gene should result in immunity to AIDS, there are also studies showing that this gene will increase the risk of sclerosis, tumors, and other autoimmune diseases (Sellebjerg et al., 2000). On top of that, some molecular biologists believe that gene editing may pollute the natural gene pool. Because we are not fully knowledgeable of the impacts that gene editing might bring, there are high risks of unexpected and off-target effects occurring.

With the examples of reproductive technologies and assisted reproductive technologies above, one might ask what the influences of reproductive technology, including legal and illegal surrogacy, on inequity and public health are? Whether assisted reproductive technology is an exploitation of women? Moreover, how to perceive the ethical issues behind emerging reproductive technology, especially regarding surrogacy and gene editing?

Problems

Andrea Whittaker published a paper on Global Social Policy in 2010 about assisted reproductive travel in Asia and pointed out that these will bring ethical, legal, and regulatory complexities (Whittaker, 2010). Many countries in the region do not have legally regulated frameworks for controversial commercial procedures such as preimplantation genetic diagnosis for baby sexual selection, and how to protect the rights and privacy for donors and surrogate mothers, or children born under surrogate circumstances. Pennings and others believed that people from different classes should have an equal level of access to assisted reproductive technology (Pennings et al., 2008) and that infertility treatments should be reimbursed. Bahamondes and others advocated that assisted reproductive technologies should be introduced into poor resource settings; otherwise, there would be an inequity between high and low classes (Bahamondes et al., 2014). Also, commercial surrogacy is a form of exploitation of females, which can be seen as unfair, such as Asian and US poor surrogate mothers. Nevertheless, in the cases where surrogacy is not even regulated or under the table altogether, this type of exploitation becomes even more severe since the surrogate mothers have no outlet for reporting abuses and no tools to protect themselves.

Assisted reproductive technologies have effects on sex ratio as well. Mingxi Chen found that the ratio of male to female infants will increase with assisted reproductive technology (Chen et al., 2017). Besides, sex selection in surrogacy, other assisted reproductive technology applications, and the popularization of prenatal fetal sex identification also have huge impacts on sex ratio. Data shows that the birth sex ratio in China has been on the rise since the mid-1980s, from 107.2:100 in 1982 to 121.2:100 in 2004. Studies project that there will be 30,000,000 more men than women in China by 2030. Assisted reproductive technology also contributes to a disproportionate number of low-birth-weight and extremely-low-birth-weight infants (Schieve et al., 2002). Patients who undergo IVF procedures are at increased risk for several adverse pregnancy outcomes as well (Schieve et al., 2004), which shows that reproductive technologies have effects on public health for not only the infants but also the mothers.

Conclusion and Things Left Unaddressed

The high cost of assisted reproductive technology leads to various forms of inequity between the wealthy and the impoverished in Asian countries. Significant compensations have lured lower-class Asian females into becoming surrogate mothers. Moreover, public health risks in societies have increased because of emerging reproductive technologies. Commercial surrogacy, especially illegal surrogacy, can be seen as oppression and exploitation of females. Management of assisted reproductive technology, especially gene editing technologies, should be strictly regulated and monitored in the future to prevent the occurrence of unknown and unintended effects at our best.

Some media outlets have referred to assisted reproduction as “helping God to create human,” but does this conform to the “laws of nature” and “social ethics?” Is there a deeper genetic cause of infertility that is unknown to us as of now? Is infertility a protective mechanism of animals’ body to prevent the transmission of certain genes? Hybrid crops and animals (e.g., rice and mule) are unable to reproduce offspring, does that suggest that genetic modification done on an organism might have potential significant influences on how reproducing has been? Do people have the right to know about applied gene editing and GMO technologies? Although many things are now labeled as Non-GMO, regulations and policies are not very strict, making it difficult for the public to judge whether many processed products contain genetically modified ingredients sometimes.

While the answers to these questions are still unclear, reproductive technology still has a long way to go. Therefore, scientists, policymakers, and the general public need to work hand in hand to create an environment for the fair and safe use of these technologies.

References

Allers, K., Hütter, G., Hofmann, J., Loddenkemper, C., Rieger, K., Thiel, E., & Schneider, T. (2011). Evidence for the cure of HIV infection by CCR5Δ32/Δ32 stem cell transplantation. Blood, 117(10), 2791–2799. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309591

Bahamondes, L., & Makuch, M. Y. (2014). Infertility care and the introduction of new reproductive technologies in poor resource settings. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 12(1), 87. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-12-87

Chen, M., Du, J., Zhao, J., Lv, H., Wang, Y., Chen, X., … Ling, X. (2017). The sex ratio of singleton and twin delivery offspring in assisted reproductive technology in China. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 7754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06152-9

Doudna, J. A., & Charpentier, E. (2014). The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science, 346(6213), 1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096

Foote, R. H. (2002). The history of artificial insemination: Selected notes and notables1. Journal of Animal Science, 80(E-suppl_2), 1–10. doi: 10.2527/animalsci2002.80e-suppl_21a

Hütter, G., Nowak, D., Mossner, M., Ganepola, S., Müßig, A., Allers, K., … Thiel, E. (2009). Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(7), 692–698. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa0802905

Schieve, L. A., Meikle, S. F., Ferre, C., Peterson, H. B., Jeng, G., & Wilcox, L. S. (2002). Low and Very Low Birth Weight in Infants Conceived with Use of Assisted Reproductive Technology. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(10), 731–737. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa010806

Schieve, L. A., Rasmussen, S. A., Buck, G. M., Schendel, D. E., Reynolds, M. A., & Wright, V. C. (2004). Are Children Born After Assisted Reproductive Technology at Increased Risk for Adverse Health Outcomes? Obstetrics & Gynecology, 103(6), 1154–1163. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000124571.04890.67

Sellebjerg, F., Madsen, H. O., Jensen, C. V., Jensen, J., & Garred, P. (2000). CCR5 Δ32, matrix metalloproteinase-9 and disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 102(1), 98–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00166-6

Surrogate motherhood is a family industry in poor Chinese villages. (2018, July 20). Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2126286/surrogate-motherhood-becomes-family-industry-poor-chinese.

Trimmings, K., & Beaumont, P. (2011). International Surrogacy Arrangements: An urgent need for Legal Regulation at the International Level. Journal of Private International Law, 7(3), 627–647. doi: 10.5235/jpil.v7n3.627

Weigel, M. (2017, October 10). Made in America. Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/144982/made-america-chinese-couples-hiring-american-women-produce-babies.

Whittaker, A. (2010). Challenges of medical travel to global regulation: A case study of reproductive travel in Asia. Global Social Policy: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Public Policy and Social Development, 10(3), 396–415. doi: 10.1177/1468018110379981