Alex Hirsch, "Mapping the Gendered Sociology of Mental Healthcare Differences in Southeast Asia"

Looking through Southeast Asia, there is a huge wealth of different cultures, histories, and languages, each of which contributes in their own way to the global community. However, in how they provide for themselves, each country in the region follows the same basic rules that any country follows: nothing exists in a vaccuum. Every decision made for the care of citizens exists as a result of what happens within the sociological structure of the country, just like how the reverse is true, and every care decision that gets made feeds back into the sociological climate. In order to better the kinds of care we provide to citizens around the world, it is important to acknowledge that as we are now, the care that we provide is uneven, and it doesn't have to be. Different kinds of citizens receive better or worse care dependent upon their identiities, especially along gendered lines.

It is important for us to ask the question: what kinds of sociological factors negatively impact and divide the care we give, and what are ways we can circumvent this while existing within any sociological ecosytem from any country across the world? We will be better able to answer this question with examples of healthcare that are highly-dependent on social norms and sociological roles. And hopefully, with a perscriptive answer to this question, we can work towards improving our attitudes towards care in the future.

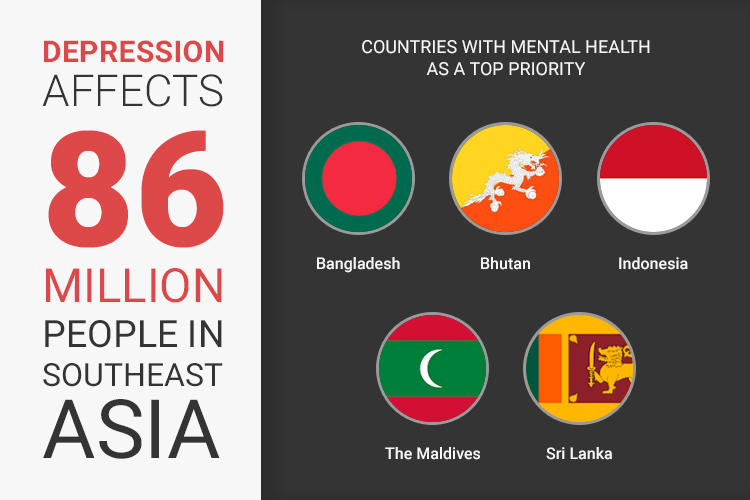

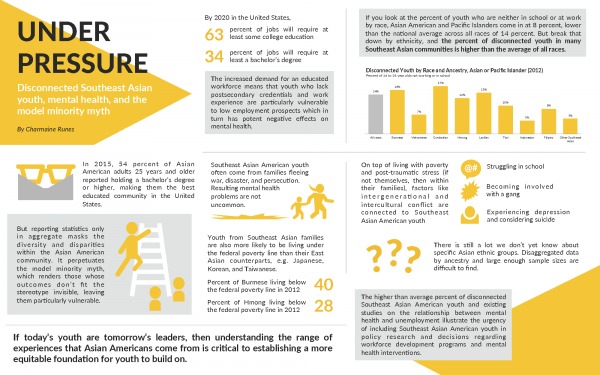

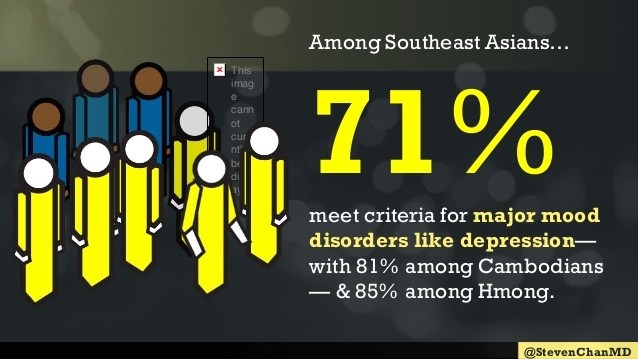

Mental health has become an issue of extreme importance in the 21st century, especially in Southeast Asia. According to studies, nearly a third of the entire population of the world that currently suffers from depression is living in South Asia. This naturally has a huge impact on the way that mental health issues are regarded by health care professionals, but it does not change the fact that mental health issues are distributed disproportionately. This issue also extends to immigrants from Southeast Asian countries, who disproportionately suffer from more mental health issues than even migrant descdendants of other Asian countries.

Disparities within mental health across gender lines is exacerbated across South Asia, and well-recorded in areas such as Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Burma. One recent study from Bangladesh showed women were twice as likely to suffer from mental health issues and three times as likely to committ suicide when compared to men.

However, the same studies that find girls significantly more likely to consider suicide compared to boys also pointed to many potential factors in upbringing that may have caused this disparity. While boys during their childhood were more likely to have received a hands-off style parenting, girls were more likely to have received a hands-on one. Girls reported that their parents knew were they were more of the time, were more involved in their schoolwork, and kept them away from substances much more strictly when compared to their male counterparts.

This speaks to a microcosm of behavioral attitudes that are known to contribute towards depression and other mental health issues, namely stress and personal freedoms. Feeling like one's personal freedoms are being restricted is a major contributing factor in developing depression, especially from a young age. Throughout Southeast Asian countries, culture tends to emphasize the roles of men more strongly than women, as most cultures have throughout the world. However with the roles of men increased, it is possible that more is expected of young girls, and therefore women throughout their lives, to perform at a higher level, and thus the extra attention.

Another important facet of the sociology that surrounds mental health issues is the changing developmental structure in Southeast Asia. When looking at Southeast Asia, the region is currently undergoing a strong urbanization proccess in the 21st century, which is changing the kinds of expecations that people have for their citizens. For example, more than ever before, it is becoming expected of women to earn money in labor jobs, a view which contrasts with traditional gender roles.

Balancing these two expectations has become a source of tension and stress in Southeast Asia, especially among women working different kinds of labor that were not traditionally available for women. Industries such as beer production, which once would never have even been considered major industries, are rapidly becoming large industries which rely upon female labor markets. While men are put under constant stress from these kinds of increased urbanization concerns, women feel the effects much more strongly because of the added sociological components, which compound the levels of stress and mental health degredation that they are suffering through.

These issues are also exacerbated by a difficult cultural climate, which is still learning to accept mental health issues as a serious problem. While a huge portion of the world's population who suffers from mental health issues resides in Southeast Asia, that problem is accentuated (and arguably fed into) by a lack of knowledge and understanding traditionally for how mental health issues plague economically developing countries. This uniquesly affects women because of the aforementioned gendered cultural stereotypes. The ways in which cultural standards differ for men and women in local Southeast Asian customs typically make it more difficult for women to transition into a more urbanized society than men, and a lack of readily available treatment options and information makes adjustment to new lifestyles even more difficult.

With this data, we can credibly demonstrate a link between gender norms and expectations, and the development of depression and other mental health issues later in life. If we can work in Southeast Asia towards removing these cultural biases and expectations that stifle and crush women more than men, we can hopefully even the gender gap in mental health issues in Southeast Asia.

When looking for the kinds of solutions that will allow public administrators and healthcare professionals to move towards productive answers to these questions about mental health, it is important to keep in mind the ways in which local cultures shape our solutions and vice versa. Without keeping our local environments in mind, the data that we have is essentially useless because of how subjective each solution is relative to the environment it is attempted in.

In particular, strong centralized healthcare systems have shown promise in evening out gendered gaps in healthcare treatments all across Asia, and by working to increase the kinds of mental health information services we provide, we can expand this already existing infrastructure into a larger system that works better for the interests of the local people in need. Turning these kinds of already-established effective infrastructure networks into creative solutions for future challenges is exactly the sort of problem-solving we need to be able to do as administrative healthcare professionals.