Sarah Wicks, "Gendered Discrimination of those Living with HIV/AIDS in China and the U.S."

AIDS patients have been discriminated against since the dawn of the AIDS epidemic in the beginning of the 1980s. At first, this discrimination was generally due to fear of getting the disease, since the modes of transmission of HIV were unknown at the time. This led to the isolation of AIDS patients and caused an "AIDS Hysteria." Now that the world knows more about the transmission of HIV, discrimination of those with HIV is often due to the perceived link between AIDS and prostitution, drug abuse, male with male sex, and sexual promiscuity that exists worldwide. The discrimination that People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) experience is divided into two categories: internal discrimination and external discrimination. Internal Discrimination consists of self-discrimination and perceived discrimination. This, for example, could be someone who feels isolated from their group of friends after receiving an HIV diagnoses. External Discrimination is received from others, including medical/reproductive health, work, and housing discrimination.

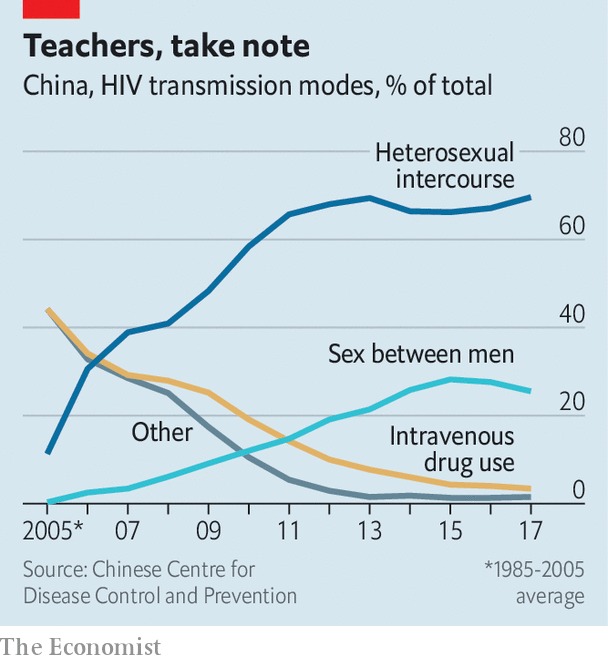

Compared to much of the world, China's HIV prevalence rate is extremely low at 0.09%. Though HIV rates in China have been rapidly increasing, it is most likely due to better detection throughout the country. According to GlobalData, Chinese men are 4 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than Chinese women. However, women with HIV/AIDS in China overall face more rights violations than their male counterparts. More women than men reported having been forced to take a blood test for HIV during a medical examination or being denied health/life insurance. Many pregnant Chinese women with HIV/AIDS have reported being refused from hospitals due to their HIV status. This is because the risk of the child having HIV is too great that many doctors do not want to be responsible for the child. Thus, women with HIV/AIDS often cannot get proper reproductive healthcare, exposing them to even more health risks. In addition to experiencing high rates of external discrimination, Chinese women with HIV/AIDS are also more likely to experience internalized discrimination. This internal discrimination is often the result of external stigma that makes one think worse about themselves. 47.6% of these women reported internalizing gossip they heard about themselves, while only 34.5% of men reported this. Experiencing internal discrimination is a large factor that leads over 50% of Chinese women with HIV/AIDS to consider suicide after being infected. This wide range of discrimination that these women face poses a serious threat to the health and wellbeing of a group that already is suffering from s potentially deadly disease.

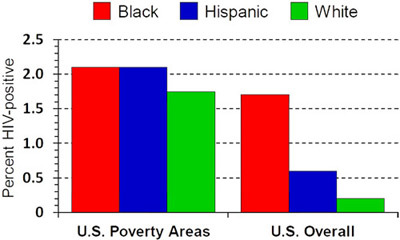

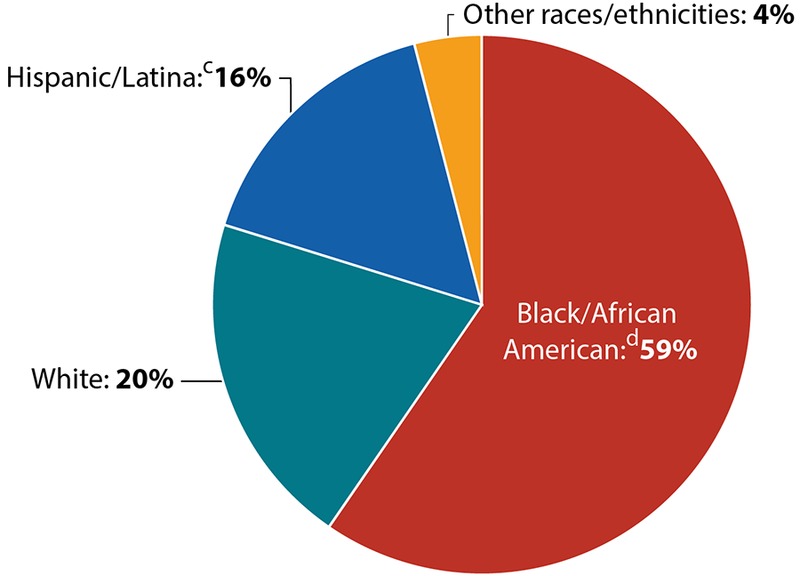

In the United States, the HIV prevalence rate is 0.34% and women make up about 25% of PLWHA. Compared to white women, women of color are especially at risk for being infected in the U.S. This is because many communities that have high populations of people of color lack resources and suffer from lack of education, economic instability, and domestic abuse. These factors, along with women generally lacking control in sexual relationships, create a "perfect storm" for HIV transmission to thrive. Though the Southern United States is home to only about 37% of the U.S, population, 52% of new AIDS cases are in the South. The high influence of conservatism in the American South places even more stigma on women with HIV/AIDS who may be seen as "morally deviant" either from sexual activity or intravenous drug use. Like China, American women with HIV/AIDS are more likely to experience internal discrimination and stigma, causing their self-worth to be greatly impacted. Since HIV disproportionately affects Black women, Latino women, and low-income women, stigma from racism, sexism, sexual identity, and engagement in sex work converge with HIV-related stigma and can worsen poor health outcomes. Food insecurity among women living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S. is much more prevalent than it is for men because of the extra stigma faced and the greater pressure to prepare food for children and the family. The extreme helplessness these women feel due to food insecurity often leads to depressive symptoms that are amplified by their HIV status.

For both the U.S. and China, the greater stigma and discrimination placed on women with HIV/AIDS stems from their sociocultural contexts. Both societies are male-dominated, and social, political, and economic gender inequality are still prevalent today. These disadvantages of women put them at greater risk for intersectional stigma, including stigma based on HIV status. In addition, self-abasement has historically been considered a female virtue in Chinese culture. This societal expectation causes an increased tendency of women blaming themselves for becoming infected, leading to more internalized stigma. Another result of the Chinese patriarchal hierarchy is that women are less likely to receive higher education. Higher education has previously been linked to less internalization of stigma and helping one cope with their HIV status. Without as equal of an opportunity to obtain a higher education, women with HIV/AIDS are more likely to internalize and be affected by stigma. In the U.S., the Christian ideal of being modest and chaste is still very much an expectation that is placed on more women than men, especially in the South. Therefore, getting HIV/AIDS is more stigmatized for a woman who may now be seen as very promiscuous or a drug user. Women with HIV/AIDS in the United States are extremely marginalized already due to many other conditions, and their HIV status adds to the discrimination against them.

The heavy stigma surrounding women with HIV/AIDS has detrimental effects regarding treatment. Antiretroviral treatment (ART) is the current most effective way to treat HIV/AIDS and has transformed the disease from incurable to controllable. Unfortunately, studies show that female bodies do not respond as effectively to antiretroviral treatment as male bodies. Women of color with HIV/AIDS also have poorer health outcomes than white women when it comes to antiretroviral treatment. However, ART is necessary for many with a positive HIV status. Many pregnant women though, especially in the U.S. and China, refuse to receive antiretroviral treatment because it would reveal their HIV status. Not receiving antiretroviral treatment makes it more likely for these women to pass HIV to their children, causing the epidemic to grow even further. In addition to this, many women believe they are not at risk to be infected by HIV because it may be seen as a "gay man disease," so they are not tested. In order to end the HIV epidemic, testing for all people, especially in low-income areas, needs to be made available and stigma about HIV status needs to end also.

Bibliography:

“AmfAR :: HIV’s Alarming Impact on Women of Color :: The Foundation for AIDS Research :: HIV / AIDS Research.” Accessed December 12, 2019. https://www.amfar.org/articles/on-the-hill/older/hiv%E2%80%99s-alarming-impact-on-women-of-color/.

Darlington, Caroline K., and Sadie P. Hutson. “Understanding HIV-Related Stigma Among Women in the Southern United States: A Literature Review.” AIDS and Behavior 21, no. 1 (January 1, 2017): 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1504-9.

Li, Li, Chunqing Lin, and Guoping Ji. “Gendered Aspects of Perceived and Internalized HIV-Related Stigma in China.” Women & Health 57, no. 9 (October 21, 2017): 1031–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2016.1235075.

“Men in China Are Four Times as Likely to Have HIV Than Women,” August 27, 2019. https://www.hivplusmag.com/prevention/2019/8/27/men-china-are-four-times-likely-have-hiv-women.

Palar, Kartika, Edward A. Frongillo, Jessica Escobar, Lila A. Sheira, Tracey E. Wilson, Adebola Adedimeji, Daniel Merenstein, et al. “Food Insecurity, Internalized Stigma, and Depressive Symptoms Among Women Living with HIV in the United States.” AIDS and Behavior 22, no. 12 (December 1, 2018): 3869–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2164-8.

“Reported Cases of HIV in China Are Rising Rapidly.” The Economist, January 12, 2019. https://www.economist.com/china/2019/01/12/reported-cases-of-hiv-in-china-are-rising-rapidly.

Rice, Whitney S., Carmen H. Logie, Tessa M. Napoles, Melonie Walcott, Abigail W. Batchelder, Mirjam-Colette Kempf, Gina M. Wingood, et al. “Perceptions of Intersectional Stigma among Diverse Women Living with HIV in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine 208 (July 1, 2018): 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.001.

Tse, Wah Fung, and Wenlong Huang. “Stigma among HIV/AIDS Patients in China.” HIV & AIDS Review. International Journal of HIV-Related Problems 16, no. 1 (2017): 11–17. https://doi.org/10.5114/hivar.2017.65921.