By Shirley Hu

"You are not in Vietnam!"

In July 2019, a viral video of a 36 year old Korean man verbally and physically assaulting his 30 year old Vietnamese wife in front of their child circulated around the web. It was secretly filmed by the wife while she endured his 3 hour long abuse. The suspect’s aggressive behavior mainly attacked the wife based on her nationality. He was arrested by the authorities soon after the video was posted online. The victim and child have been moved to a shelter for protection and she is receiving medical treatment for her injuries. This case sparked public outrage against the government for its inability to protect migrant women from domestic abuse. Much of the criticism is directed toward the lax consequences of South Korean laws for such crimes and prevention of such from occurring. This is not an isolated case as reported by a survey by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea (NHRCK) in June 2018, “42.1%, report[ing] experience with domestic abuse” out of the 920 married female migrants who responded to the survey (Seon). With such a high percentage for those who responded to this survey, it could possibly be even higher if accounting for those who chose to remain silent.

Context

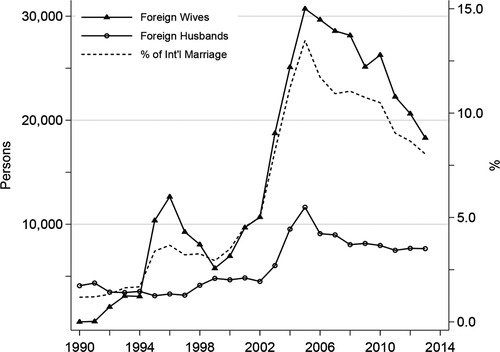

Since the early 1990s, there’s a long history of cross border marriages in South Korea, not just between Korean men and foreign brides but also between Korean women and foreign husbands. Particularly large scale international marriage migrations with developing Asian countries near South Korea such as China, Vietnam and the Philippines.

-

"[R]oughly 10 percent of all annual marriages–and a third of all marriages in rural areas–since the late 1990s have involved foreign nationals, most of whom are women from Southeast Asian countries (Jones & Shen, 2008; Kim, Yang, & Torneo, 2014).”

-

"Although international marriages accounted for only 1.2 percent of marriages in 1990, they represented 13.6 percent in 2006, a ten-fold increase.”

-

Since the 1970s, rural to urban land migration of young South Korean women for job opportunities, higher education, and husbands. Consequently ties in hand with more postponement or rejection of marriage by Korean women.

To counter issue of sex-ratio imbalance in rural marriage market communities, the government endorsed cross-border marriages.

It is important to remember that although domestic abuse may seem highly prevalent in cross border marriages, not all cross border marriages are arranged nor are they involved with domestic abuse. There are cases these intercultural marriages are positive experiences when there is a good marital relationship between the spouses even when migrant wives face challenging circumstances such as discrimination or language barriers.

Domestic abuse in Cross-Border Marriage Migration : The Gap Between Ideal and Reality

The arrangement process of marriage through brokers was malicious because there were many fees involved and often the spouses discovered a discrepancy between the information provided by the agencies and the reality. According to a fact-finding survey of international marriage brokerage carried out by South Korea’s Ministry of Gender Equality and Family in 2017 (covering 1,010 South Korean users and 514 marriage migrants), the average length of time between the prospective partners’ first meeting and their actual marriage was just 4.4 days. Marriages were commodified and exploited by marriage brokers who took advantage of the lax regulation enforcement and the desires of the people involved.

Through an analysis of a data study from vital statistics on marriage from Statistics Korea, and two waves of the National Survey of Multicultural Families in Korea (NSMF) from 2010 to 2015 the typical Korean nationals engaging in these international marriages were males “who are in their 40s, have less than a high school education, live in rural areas, and are farmers or labour-ers.” Because of the Korean grooms’ unattractive marginal socioeconomic position in the domestic marriage market, it is easier to find a spouse through these international marriages since many of the migrant women’s purpose was to escape poverty in their home country.

However issues arise from these arranged marriages because often “... Korean grooms who married foreign brides, about 85 percent of them were older than their wives and 53 percent were at least 10 years older.” Beside the age gap, “[m]ost of the couples (90 percent of the respondent couples according to Seol’s survey in 2006) use Korean for communication” which another barrier in terms of communication difficulties between the spouses. Because of the many faults in these commodified marriages, they attribute to the high rates of domestic abuse in the international marriages. “Some men engage in physical and emotional abuse, critics say, out of frustration that the woman they’d “spent all that money to buy” wouldn’t bend to their will.”

Gender and Power imbalance in migrant marriages

Migrant marriages generally constrict migrant wives into a vulnerable position of only being able to depend on their Korean national husbands and husband’s family. They first enter these marriages being sold with “the submissive, virginal, and virtuous image” that can fulfill the traditional roles of a Korean female by South Korean marriage agencies. This image is important because migrant mothers in South Korea are expected to raise “Korean” children.

There are many Multicultural Family Support Centres established by the South Korean government to support the wives through various programs that “consist of Korean language and cooking classes, job training, counseling services, cultural adjustment training, and support for social networking” (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family 2013, 18). These programs are in preparation to create the “model migrant bride,” a dutiful and sacrificing bride who fulfilled the caring obligation for her marital family and the rehabilitation of a patriarchal family in South Korea.”

There is little freedom for migrant wives as daughter-in-laws because of the family dynamic construction as “according to a 2006 survey, more cross-border married couples were found living with the family of the husband than previous years: 14 percent of these couples in cities and 45 percent of the couples in rural areas live with extended family (Seol 2006, 38). This is high compared to only 6.2 percent of Korean families who live with their in-laws (Statistics Korea 2011).”

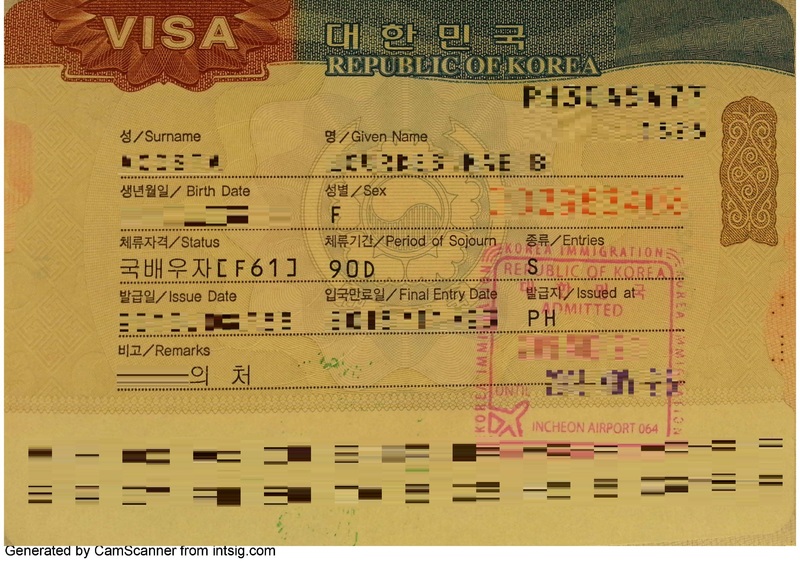

Furthermore for migrant wives to attain residency rights, it is vital for the renewal of their temporary spousal F-6 visa by their Korean husbands guaranteeing communication capability. South Korean husbands and families can manipulate the migrants through this legal authority of stopping them from obtaining citizenship or visa status.

However it is interesting to note that “the Korean language requirement is waived if the multicultural couple [has] a child together. This practice shows the state’s recognition of the “contribution of international marriage” to reproduction of the next generation to iron out recent low birth rates." What also constrains migrant women in these marriages is the favoritism toward Korean fathers because “custody rights are usually granted to the father in case of divorce, especially if the father is a citizen and the mother is not. After her marriage ends, she may have difficulties in ensuring her settlement in Korea unless she can prove abuse, abandonment, or violence by the husband.”

What does the government do for migrant women and is it enough?

The South Korean government has initiated many laws and acts such as the Multicultural Family Support Law, the “Basic Law Regarding the Better Treatment of Foreign Residents in Korea,” the Nationality Act, National Basic Living Security Law, Immigration Control Act, and the Framework Act on Treatment of Foreigners to help multicultural migrant families.

However looking more closely at these government-driven initiatives, it is revealed that these laws are primarily targeted toward migrant women to resolve Korea’s problems with the “bride drought” and “care drain.” Most of the benefits only go toward those that start a family in South Korea and while “the multicultural centers [do] provide practical classes, such as Korean language instruction, they do so only marginally. For example, only 400 hours a year of language education is guaranteed at any particular center, about an hour a day." These centers only help resolve superficial level problems and lack giving attention to more important matters such as raising awareness and educating migrant women about their rights.

This indifference toward the migrant wives’ safety and legal ability is also reflected in the lenient punishments of domestic violence cases; “[o]f reported domestic violence cases for the past five years, only 13% saw arrests, 8.5% resulted in an indictment, and just 0.9% drew an actual prison sentence." Also “[i]n South Korea, a total of 123 women were killed by their husbands or partners in 2013, according to the Korea Women’s Hotline, a nationwide women’s group that works to stop domestic violence. Foreigners account for just 2.5 percent of the population in South Korea, but with a comparatively high number of deaths involving foreign women since 2012, experts from government and nongovernment organizations agree that migrant women here are particularly at risk to domestic violence."

Migrant women are limited in sources and knowledge of how to attain help which is why "the victims of abuse by spouse usually seek help from women's rights organisations or multicultural family support centres rather than taking legal steps" as reported by an official at the Vietnamese Women's Union in South Korea.

Bibliography

Ahn, Yonson. “Gender Under Reconstruction: Negotiating Gender Identities of Marriage Migrant Women from Asia in South Korea.” In After-Development Dynamics. Oxford University Press, 2015.

BBC. 2019. “South Korea Shocked by Abuse of ‘marriage Migrants’ - BBC News,” July 10, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-48917935.

Iglauer, Philip. 2015. “South Korea’s Foreign Bride Problem.” News. The Diplomat. January 29, 2015. https://thediplomat.com/2015/01/south-koreas-foreign-bride-problem/.

Kang, Seung Woo. 2019. “Top Court Rules in Favor of Migrant Wives.” The Korea Times, July 10, 2019. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2019/07/177_272079.html.

Kim, Keuntae. “Cross‐Border Marriages in South Korea and the Challenges of Rising Multiculturalism.” International Migration 55, no. 3 (June 2017): 74–88.

“Migrant Wife Is Model Daughter-in-Law in South Korea.” 2019. News. The Straits Times. November 14, 2019. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/south-koreas-model-daughter-in-law.

Seon, Dam-eun. 2019. “A Look into S. Korea’s International Marriage Brokers and ‘Bride Buying.’” News. The Hankyoreh. July 12, 2019. http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/901613.html.

Seon, Dam-eun. 2019. “Video of Migrant Woman Being Abused by Husband Incites Public Outrage.” Hankyoreh, July 8, 2019. http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/900962.html.

Sung, Miai, Chin, Meejung, Lee, Jaerim, and Lee, Soyoung. “Ethnic Variations in Factors Contributing to the Life Satisfaction of Migrant Wives in South Korea.” Family Relations 62, no. 1 (February 2013): 226–240.