Sarp's Website Review: Turkey Cultural Heritage Map

Introduction

The website I will be analyzing for Website Review is Turkey Cultural Heritage Map, a cultural digital mapping project. Based on archive and field research, the project maps the public buildings owned and used by non-Muslim ethnic groups on the borders of Turkey in the Ottoman and Republican Era.

Purpose of the Project

Turkey Cultural Heritage Map is one of the results of the cultural heritage inventory carried out by the Hrant Dink Foundation since 2014. The cultural heritage of the Armenian, Greek, Assyrian, and Jewish communities is documented on the map, and the visibility of the multiculturalism created by various peoples in Anatolia is provided. Basic information about public buildings such as churches, schools, monasteries, cemeteries, synagogues, and hospitals, compiled from multiple archives and printed primary and secondary sources, is presented with an online map. Turkey Cultural Heritage Map is a work in progress.

In addition to the inventory breakdown, the map also includes the Field Stories layer, which reflects the field findings and research experience focused on the creative reuse of memory spaces. Research topics, in which Armenian culture in Anatolia and local views and suggestions about the place are discussed together, are presented in the form of stories and city tours, accompanied by 360-degree images, videos, sounds, and photographs. Going beyond the tangible cultural heritage, this study, which deals with the intangible cultural heritage, not only places the places where Armenians lived in Anatolia from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic on the map in an interactive way but also aimed to revive the memory that has been subject to extinction by using new media.[1]

For those unfamiliar with the name, Hrant Dink is a Turkish Armenian journalist murdered in 2007 by Ogun Samast, who was under 18 at the time, in front of the building of the Agos newspaper, where he was the editor-in-chief. The Hrant Dink Foundation is an organization that was established in the same year to keep Dink's memories, struggles, and dreams alive. The missions of the Foundation are to create equal opportunities for youth and children, to contribute to Turkey's democratization, to protect cultural diversity and richness, to develop cultural relations between Turkey, Armenia, and Europe, to conduct history studies free from racism and nationalism, and to collect the articles, documents, and images about Hrant Dink.[2] In addition, a street in Lyon and a street in Sur district of Diyarbakir, where Muslims and Assyrians lived together, were named after Hrant Dink.

Design and Functionality

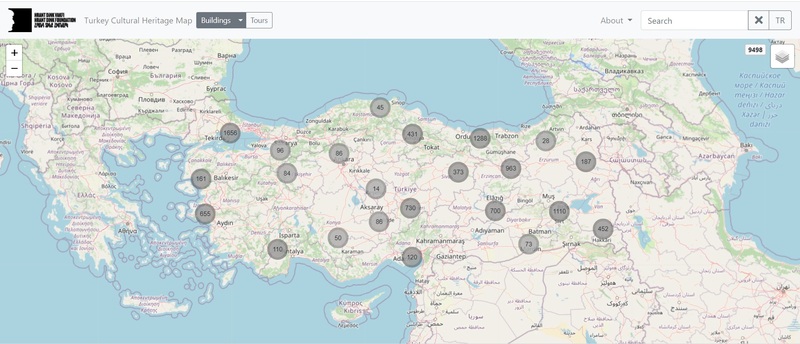

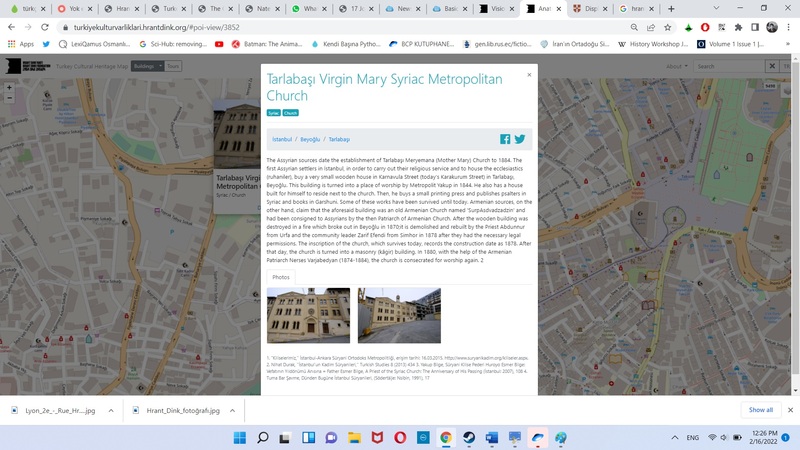

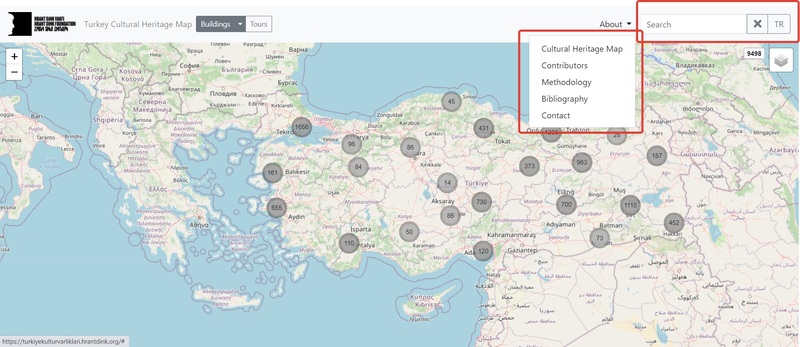

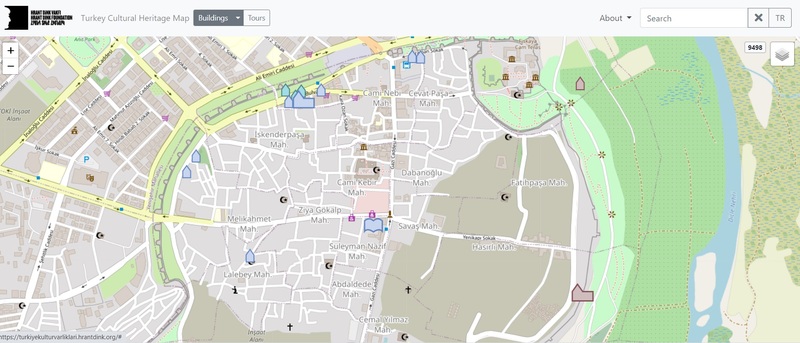

On the project’s homepage, there are various points on a Turkey map and numbers inside these points. While these points show the regions where the buildings are located, their numbers express the number of buildings in that area. If a specific point on the map is zoomed in, the points and numbers are reshaped according to the distribution of buildings in that area. When we get closer, we can see the individual buildings in the region. When we click on the small icons representing the buildings, we can access detailed information about that building. There is information such as the name of the building, its history, current status, type, the purpose of use, the exact location, which community uses it, and a reference. It is also possible to access photos, videos, or 360-degree panoramas of buildings in this way.

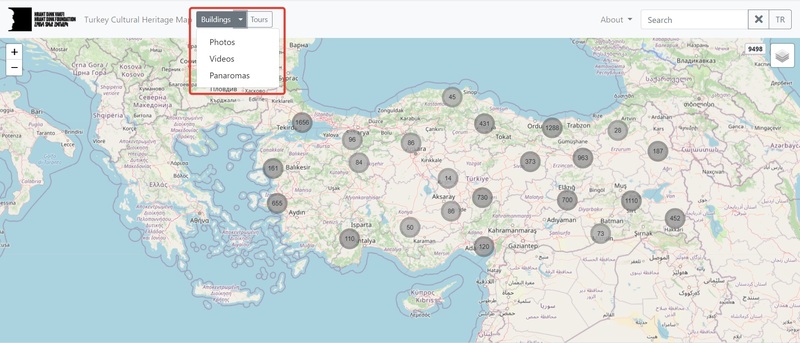

By clicking on the buildings tab in the upper left corner of the map, it is possible to access only the records containing photographs, videos, or panoramas. The About tab contains detailed information about the project, contributors, study methodology, bibliography, and contact information in the upper right corner. When we click on each of them, a pop-up opens, and the relevant information comes to us. It is possible to search for buildings individually with the search tab next to it, and there is a button that allows language switching between English and Turkish.

The map is a successful study regarding ease of use and content. The fact that it not only gives written information about the buildings but also supports them with visuals offers the chance to observe the architectural structures and shows how this cultural heritage has not been preserved. Many buildings are in derelict condition, and buildings that are not even in the inventory of the Ministry of Culture have been identified. Also, I think such a study on non-Muslim buildings or cultural heritage in Anatolia is a first. Another valuable point of the work is that not only project researchers but also independent users can contribute to the project by using the information and images they have. There are options for each building on the site to 'add a photo,’ 'add information,’ and 'change information.’ Anyone who wishes will be able to send their resources, photos, and information. With the 'Add new building' option, information and pictures can be sent about a building that is not on the list.

Historiography

The importance of the project in terms of historiography is more than one. First of all, as mentioned above, such an inclusive study on non-Muslim public spaces in Turkey is being conducted for the first time. While there are individual secondary sources on a particular ethnic group and primary sources on buildings, bringing these primary and secondary sources together is a big step. Thus, public areas that do not exist in the state’s official records or do not have information in secondary sources are identified and open to public access. One of the researchers clearly expresses this situation in the field studies they carried out after the inventory work: "When we started the second phase, the Armenians had around 4,000 structures. The Greeks had around 2,000 structures. As a result of the study, the structures of the Greeks reached 4,000. Nearly 700 structures of the Assyrians were revealed. At the beginning of Kayseri, there were 250 buildings. When he started to work focused on Kayseri, the figure increased to 350. When we got to the field, we reached 400. The numbers increase when focused work begins.”[3]

Secondly, it is a generally accepted historical knowledge that with the emergence of nation-states, how nation-states assimilated or destroyed other cultural elements in the region where they were established.[4] In Turkey, the story is not much different from this. While many different ethnic groups live in Turkey’s borders, today, there is a predominantly Turkish-Muslim population structure due to population exchanges, deportations, assimilation policies, and massacres. Seeing the multitude of buildings and public spaces left by these ethnic groups that were somehow destroyed and witnessing today’s devastation clearly shows the extent of the cultural change.

Suggestions

I think that this project can be beneficial for the 'Mapping Violence: War and Redevelopment in Sur, Turkey' project in two ways. Just as this map marks the public areas, the points where the clashes took place and barricades were set up in the Sur, and the buildings destroyed by the security forces can be marked on the map. Videos, photos, and panoramas can be added to these marked points and visually shown to those who examine the project. Secondly, in their presentations, they said that the destruction in Sur had cultural reasons as well as economic reasons. If the state carries out an assimilation program by deliberately destroying Kurdish cultural assets in the region, this project can contribute to showing that this is not only for Kurds. Thanks to this project, the cultural heritage of Armenian, Assyrian and Jewish communities in Diyarbakir can be discovered once again. The present conditions of the buildings of these communities may enable us to consider the dimensions of cultural destruction in a broader framework.

[1] “Turkey Cultural Heritage Map”, Hrant Dink Foundation, accessed 15 February 2022, https://turkiyekulturvarliklari.hrantdink.org/#content-view/1

[2] “Vision Mission”, Hrant Dink Foundation, accessed 15 February 2022, https://hrantdink.org/en/about-us/vission-mission

[3] Uygar Gultekin, “Yok edilen uygarlığın kültür envanteri gün yüzüne çıktı”, Agos, February 5, 2016, http://www.agos.com.tr/tr/yazi/14270/yok-edilen-uygarligin-kultur-envanteri-gun-yuzune-cikti

[4] For an overview about the displacement and dispossession in the Modern Middle East see; Chatty, Dawn. Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. The Contemporary Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511844812.