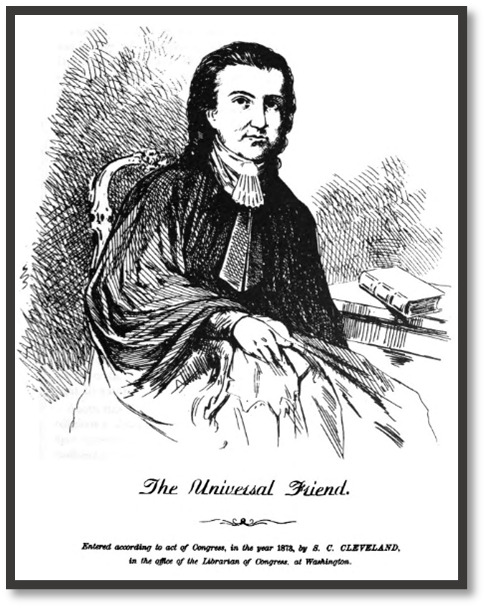

"The Person Called the Universal Friend"

Language, Divinity, and Gender in the Society of the Public Universal Friend

Jemima Wilkinson was born in the 1750s to a Quaker family living in Cumberland, Rhode Island. While this rough decade of birth raises no particular controversy, the same cannot be said for discussing the decade – or even century – in which Wilkinson died. Officially, Jemima Wilkinson died in 1819 in Jerusalem, New York, a community founded by the Society of the Public Universal Friend. If you were to ask the member of that society when it was that Jemima Wilkinson died, however, it is more likely that they would say it was in 1776 after an American naval ship brought a fever to the town. In this version of Jemima Wilkinson’s life and death, the young Rhode Island Quaker died late in that year, only to rise again, not as Jemima Wilkinson, but as the Public Universal Friend.

This version of the Friend's origins is most directly recorded in a document found slipped into the pages of the Friend’s Bible, wherein the story of the illness, holy visions, and subsequent death of Jemima Wilkinson and birth of the Public Universal Friend were preserved. It is perhaps the most explicit defining of the Public Universal Friend found anywhere in surviving sources, relaying what Wilkinson was supposed to have witnessed in her final moments before her body was left an empty vessel for the Lord to refill: “And the Angels said, The Spirit of Life from God, had descended to earth to warn a lost and guilty, perishing dying World, to flee from the wrath which is to come; and to give an Invitation to the lost Sheep of the house of Israel to come home; and was waiting to assume the Body which God had prepared for the Spirit to dwell in.” The account goes on to state that between nine and ten in the morning, Wilkinson “dropt the dying flesh and yielded up the Ghost,” making it so that “the Spirit” could then take “full possession of the Body it now animates.”(1)

Following that transition from human to divine, the Friend would insisted upon being understood only as the Friend. As the Friend went on to found and lead the religious community bearing the same name - the Society of the Public Universal Friend - the importance that identity would become all the more important. This strict understanding of the Friend's identity extended to the Society’s linguistic practices, with followers refusing to identify the Friend in any way as Jemima Wilkinson and, even more uniquely, refusing to use third-person pronouns to refer to the Friend. Throughout documents produced by and within the Society, the Friend is referred to exclusively using this transitioned identity, including times in which a pronoun would typically replace one’s name, with near if not total exclusivity. As just one example among many, Sarah Richards – an early and high-ranking member of the Society – structured her references to the Friend in her recording of a much longer fantastical dream from 1800 as, “…I saw the Friend lift up the Friends eyes towards Heaven.” (2) Richards, like other members of the Society, used pronouns in all other situations, whether for other people, angels, Jesus Christ, God, or any sort of otherworldly being, but never for the Friend and with the same consistency that the Jemima Wilkinson identity was rejected. Within the Society, there was no “Jemima Wilkinson,” the Friend was not “her,” and those who transgressed this linguistic rule would be corrected and admonished, even if they were outsiders who were neither aware of the practice nor followers of the figure it was built around. As this brief analysis will focus on however, adherence to upholding the Friend's identity consistently put the Society at legal risk. Ultimately, the Society was forced to carefully balance the conformity required to protect their continued survival with the resistance inherent in upholding the Friend's divinity and gender ambiguity.

The last will and testament of the Public Universal Friend survives in a copy taken down by John Briggs in 1820, two years after the original copy was created. Briggs was a witness for a section of the will and, as indicated also by his notes from Society meetings in the early 19th century, acted as a record keeper at times for the Society. The document itself reads as standard in preparing for the Friend’s death, assigning Rachel and Margaret Malin as both inheritors and executors of the Friend’s property and estate. What is, then, not standard, is the way in which this legal document works to both uphold and compromise the Society’s creedal language. The opening lines read: “The Last will and Testament of the Person Called the Universal Friend of Jerusalem in the County of Ontario and State of New York who in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy six was called Jemima Wilkinson and ever since that time the Universal Friend a new name which the mouth of the Lord Hath named…” The owner of the will is always defined by this divine, ambiguously gendered, and transitioned identity, with some version of this formula used in any place where an individual’s name would be required. While this phrasing stands out slightly against the broader backdrop of the Society’s linguistic practices in including the name of Jemima Wilkinson, it is perfectly in line with the ways in which the Society had to adapt those practices to conform to legal requirements while still upholding their own creed.

Footnotes

1. “A Memorandum of the introduction of that fatal Fever,” in Herbert A. Wisbey, Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1964), 13.

2. Jemima Wilkinson Papers, #357. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.