Geoffrey Ramirez: The Quipu Project Website Review

Introduction

Created as a digital documentary and online archive, the Quipu Project pulls double duty as an interactive documentary and online archive for numerous phone interviews. Directed by Maria Court and Rosemarie Lerner, with academic support from Matthew Brown and Karen Tucker of the University of Bristol, The Quipu Project presents the narratives of over one hundred Peruvian women who were forcibly sterilized under President Alberto Fujimori in the mid-1990s. Designed as an interactive documentary, the audience is guided to explore individual phone interviews to understand the personal cost of the state’s sterilization program and its effects on the indigenous population.

Though largely focused on promoting awareness and maintaining a collective cultural memory for the Peruvian community, the site offers several important lessons and design aspects which can be incorporated into our own project. Its design around an Incan cultural recording device, the care in providing translated narratives, and the prompt for the audience to act or react to the narratives presented offers interesting ideas to take forward as we move into the Mapping Violence project properly.

Historiography

In 1995, President Alberto Fujimori’s government launched an extensive family planning program which was billed as promoting “women’s development and empowerment.”[1] Two years later, reports came in that Peruvian woman were being forcibly sterilized, often without proper medical attention.[2] Investigations on the matter uncovered that around “300,000 women and men” were sterilized from 1996 to 2000, many being illiterate and indigenous members of rural communities.[3] Internal reviews of the Peruvian state often overlooked this planning policy, focusing instead on internal violence and other human rights violations, resulting in a loss of the collective and state memory of the incident.[4] The narratives presented in the project thus act to recenter the collective Peruvian memory back onto the 1990s and these rural communities, reintegrating them into the national memory.

Purpose

The main goal of this site is to preserve and present the cultural memory of the sterilized women and communities. Contesting the intention of the state to forget this incident, the project seeks to revitalize interest and awareness in this recent history. Thus, the site seeks to act as a piece of activism and a means of preservation.

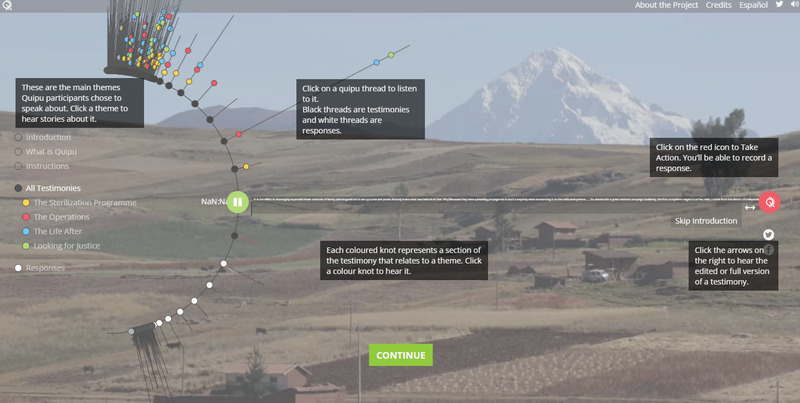

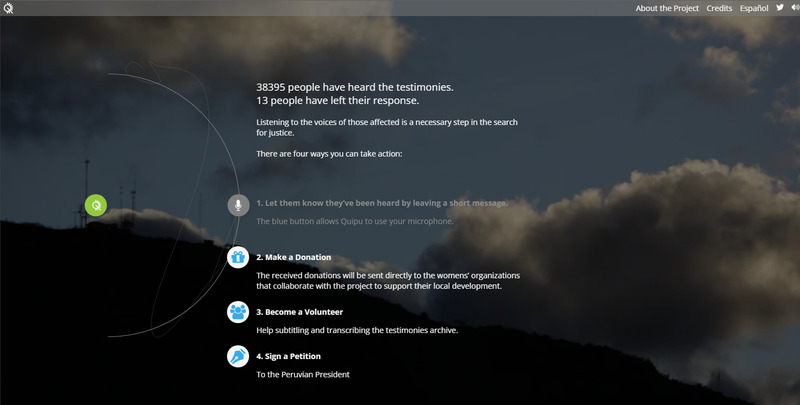

In the case of the former, the goal is largely successful. The entire site is designed around an Incan means of record keeping. The audience is invited to explore threads of narratives with each strand representing a single woman’s account of sterilization. Specific knots in these threads are color coded to indicate details in the narrators account that describe the program, the operation they underwent, how life changed after sterilization, and if they were seeking justice for what happened to them.[5] Beyond the introductory text and these description keys, the audience is left to explore the accounts on their own time. Narratives automatically play on their own, but the audience can move freely ahead to specific sections or onto other narratives at their own pace. In the end, the audience is left to grapple with the weight of the testimonies with little interpretation. Until 2017, the audience could record responses to the narratives which then appeared on the site showcasing the global response to these women’s stories. On a whole, the site was able to raises awareness while also showing the visible evidence for it on the site itself.

While it succeeds as a piece of activism, the preservation part needs to be reconsidered. The narratives themselves are amazing, but difficult to navigate properly and while there is transcribed text it cannot be accessed on its own or rewound without reloading the site. So, while the narratives are preserved, they are not easily accessible for researchers. As a cultural archive, the site is amazing. But as a functional archive, several aspects of it need to be reconsidered. The Oral History Association, for instance, notes that proper preservation of oral histories needs metadata to be properly recorded. Technology used needs to be disclosed, proper metadata needs recording, and full transcriptions should be accessible.[6] Though narratives sometimes give details on locations where narrators were from, the lack of proper metadata and access to transcriptions weakens the usefulness of the site as an archive.

In a sense, it succeeds as a cultural archive, but not an academic one.

Design and Functionality

The entire website is designed to compliment its purpose. As both a cultural piece of record keeping, and a means of empowerment, the design works wonders as a means of activism even if it is not a concise means of preservation. Text is available in English and Spanish, and everything is accessible through mouse movements and not scrolling, allowing for greater access for the audience. Images are constantly displayed behind the narratives, giving a sense of space, and characterizing the voices being listened to. While some threads are difficult to access due to how clustered they are on the ring, nothing is overly clunky or off-putting about the site. It functions as a quipu would in both how narratives are threaded, in how the site is navigated, and in how this information is recorded. As a whole, the site considers culture, purpose, and user ease in a way that is both brilliant and intimidating to replicate.

While our early stage of Mapping Violence will not look nearly as polished, we can still incorporate aspects of this design into our final product. The streets of Sur were an important aspect of the city before their destruction, for instance, so incorporating that atmosphere of narrowness in the website’s navigation or visual design may lend the narrative greater strength after those streets were widened for tanks. Likewise, ensuring that text is available in Turkish, and English can ensure a broader audience can access the media. Finally, while keeping every item accessible on a single page may be too difficult to pull off, having an optimized means of navigating information all at once may be something to consider. Ensuring that separate pages exist for metadata and full transcriptions will likewise ensure that our site can act both as a piece of activism and a proper archive.

Our Purposes

The Quipu Project works well as a story telling device, but not as a means of proper academic research. It shares personal stories about an overlooked part of Peruvian history while simultaneously raising awareness of this history and its ongoing ramifications. While it preserves amazing oral histories, they are not archived in a way that is conducive to proper research. It delves into an event in history but does not describe the lead up to that event nor what prompted the project to come into existence beyond as a means of activism.

Considering these critiques, we must also consider what the goal of the site is to be. If it is to act as a site of awareness of archiving, then it must be designed to ensure both goals are treated respectfully. We must ensure the site is accessible, engaging, and designed to support the story being told while also maintaining the usefulness of a proper archive. That can easily be done by creating separate pages or tabs to separate the interactive piece from the nitty-gritty without treading on either space. Likewise, ensuring there is a space for people to react or record their responses to the site will only benefit it. While these responses need to be properly moderated, much like the Quipu project, they can be time limited to prevent the space from falling into disarray. Finally, the potential political repercussions for putting information onto the web must also be considered. Much like the Quipu project, identities and locations can be hidden for the protection of narrators, though we would have to deal with how that would translate in the archived pages. That is an ethnical and practical debate which potentially cannot be solved in this semester but is something to consider going forward.

[1] Matthew Brown and Karen Tucker, “Unconsented Sterilisation, Participatory Story-Telling, and Digital Counter-Memory in Peru,” Antipode vol. 49, no. 5 (2017): 1188.

[2] Brown and Tucker, “Unconsented Sterilisation,” 1188.

[3] Brown and Tucker, “Unconsented Sterilisation,” 1189.

[4] Brown and Tucker, “Unconsented Sterilisation,” 1189 – 1190.

[5] Maria Court and Rosemarie Lerner, The Quipu Project, accessed Februery 16, 2022, https://interactive.quipu-project.com/#/en/quipu/listen/intronode?currentTime=0&view=thread.

[6] “Archiving Oral History,” Oral History Association, October 2019, https://www.oralhistory.org/archives-principles-and-best-practices-overview/.

Bibliography:

Court, Maria and Rosemarie Lerner. The Quipu Project. Accessed Febury 16, 2022. https://interactive.quipu-project.com/#/en/quipu/intro.

Brown, Matthew and Karen Tucker. "Unconsented Sterilisation, Participatory Story-Telling, and Digital Coutner-Memory in Peru." Antipode, vol. 49, no. 5 (2017): 1186 - 1203.

"Archiving Oral History," Oral History Association, October 2019, https://www.oralhistory.org/archives-principles-and-best-practices-overview/.